-

Old red eyes is back (Andrew)

Phil Noble has certainly done his job well. Paparazzi will paparazz, we can’t expect anything different from him. But there is one question I would put to him.

-

Prosper UK and David Gauke: Good luck, I guess

One might regard their support of Prosper UK with scepticism: is it driven by principle or opportunism?

-

Unfinished business

I’m lying down on the road. All is well. I can stop now. There’s a moment of sweet surrender. All is well.

-

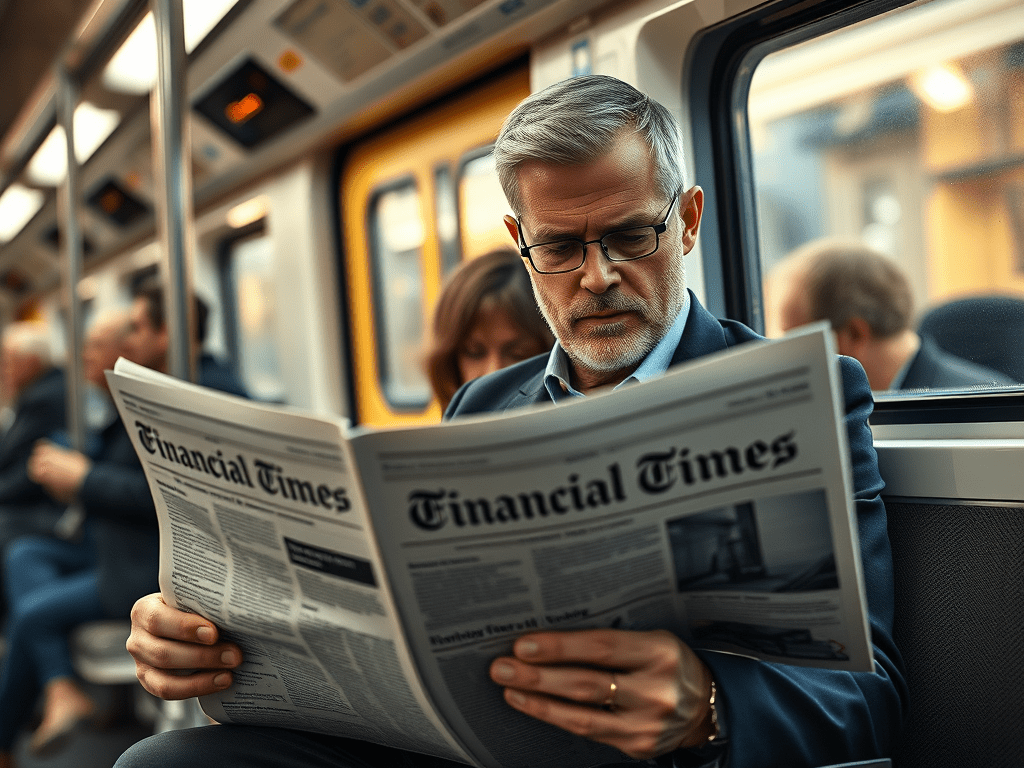

The Chorleywood Thunderer

The majority of my letters to the Financial Times made it into print: ten were published out of perhaps fifteen between 2010 and 2015. This might be because they were well-written, relevant, incisive and witty. Or maybe the FT was just a sucker for free content.

-

Good and bad in disposable TV

I have never been able to watch more than two minutes of this hyped up, whooping celebration of mediocrity and third division “celebrities”.

-

Navigating Politics in International Athletics 1960-84 by Fred Holder

Fred Holder was Honorary Secretary of the International Amateur Athletic Federation from 1960-1984. In 1998 he wrote a fascinating insider’s account of this turbulent period of athletics, never before made public.

-

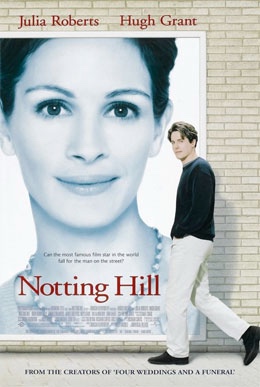

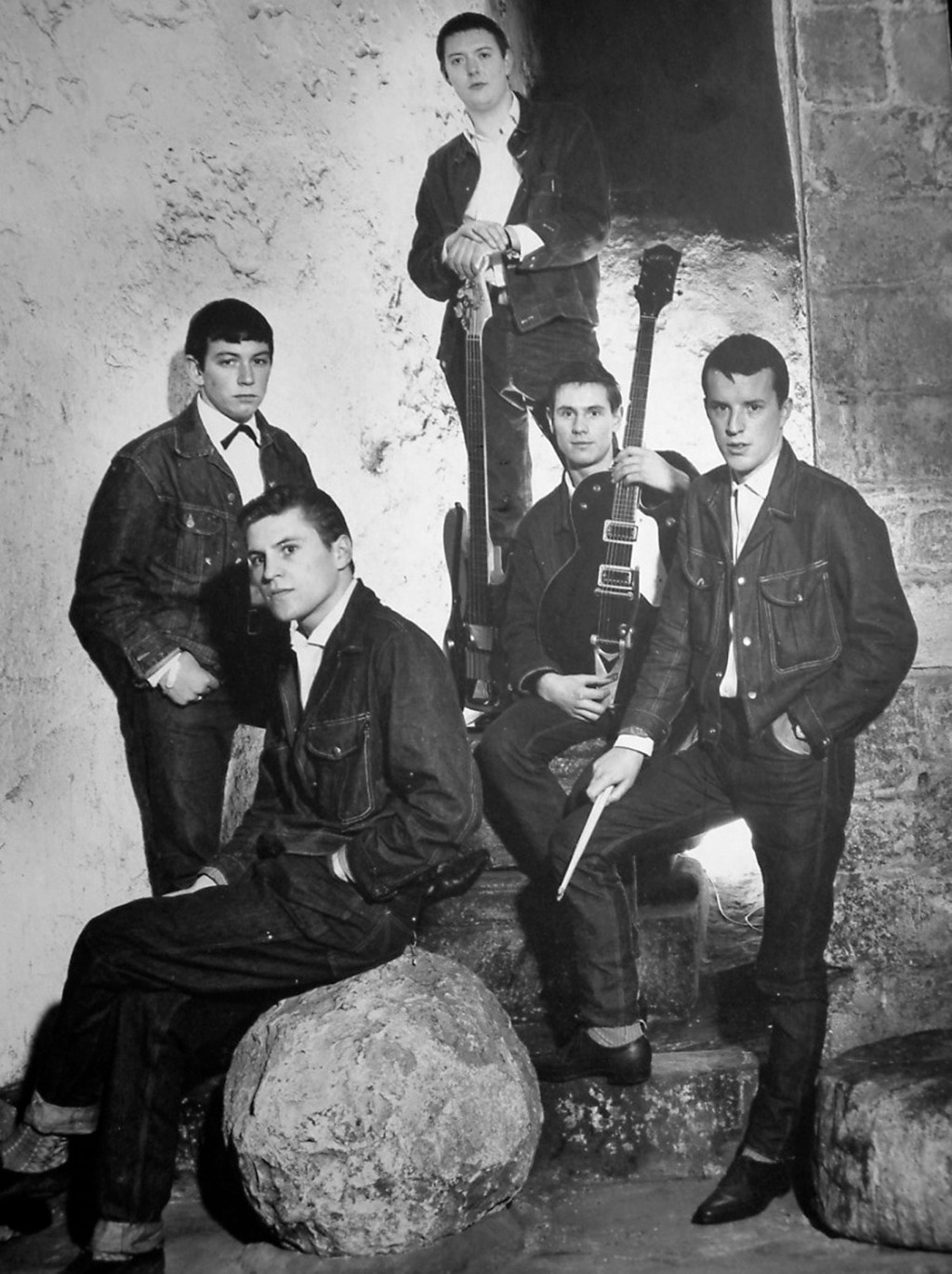

At the birth of The Animals

“I loved Newcastle so much that I failed my exams. I probably should not have gone clubbing during re-sits with Alan Price and Eric Burdon before they got together as The Animals and released House of the Rising Sun.” Wait, what???!!!

-

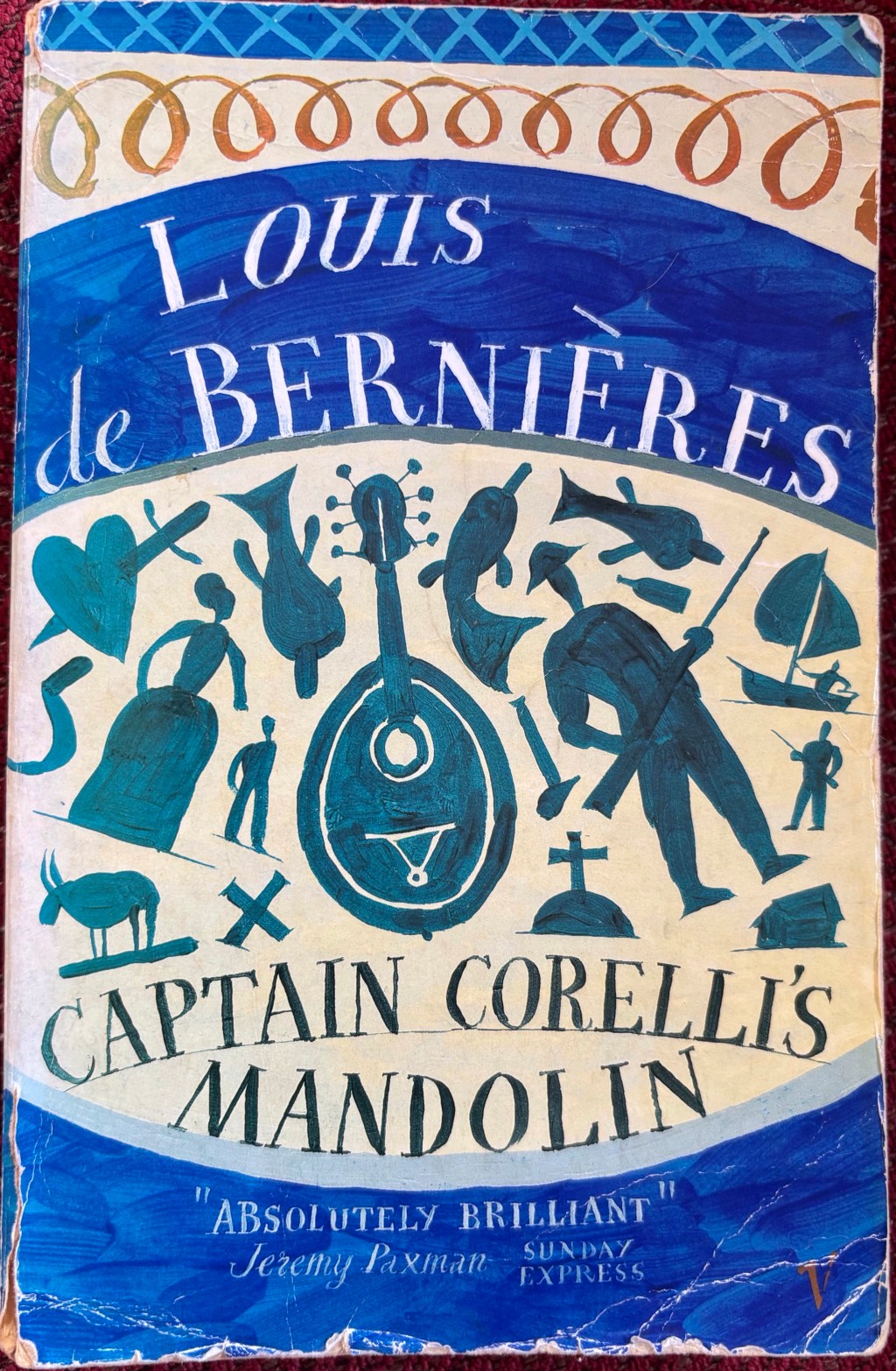

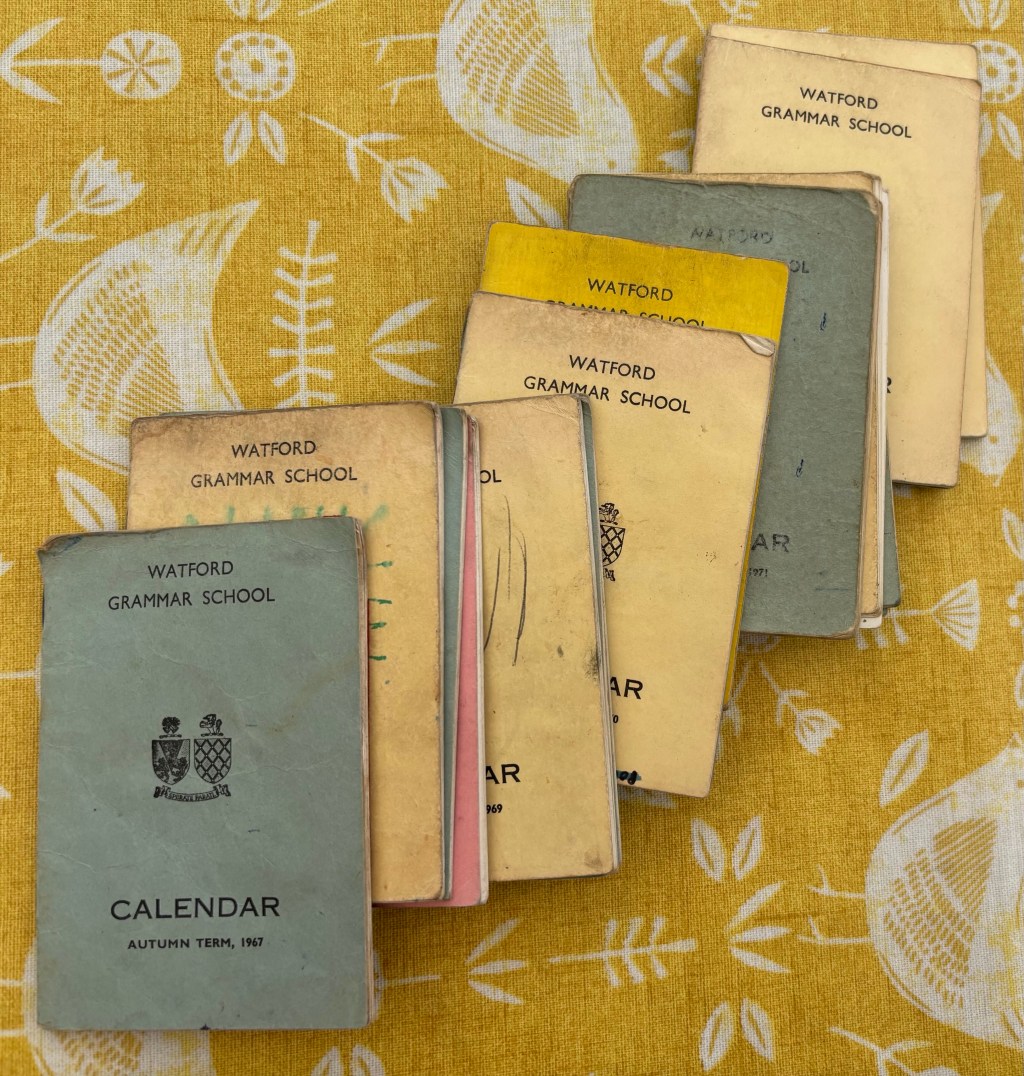

A hoarder? Excuse me, I’m an archivist.

I have a schedule listing the A-level and S-Level results of my entire 6th-form cohort: that has enabled me to intimidate former schoolmates with my knowledge of their shortcomings for half a century.

-

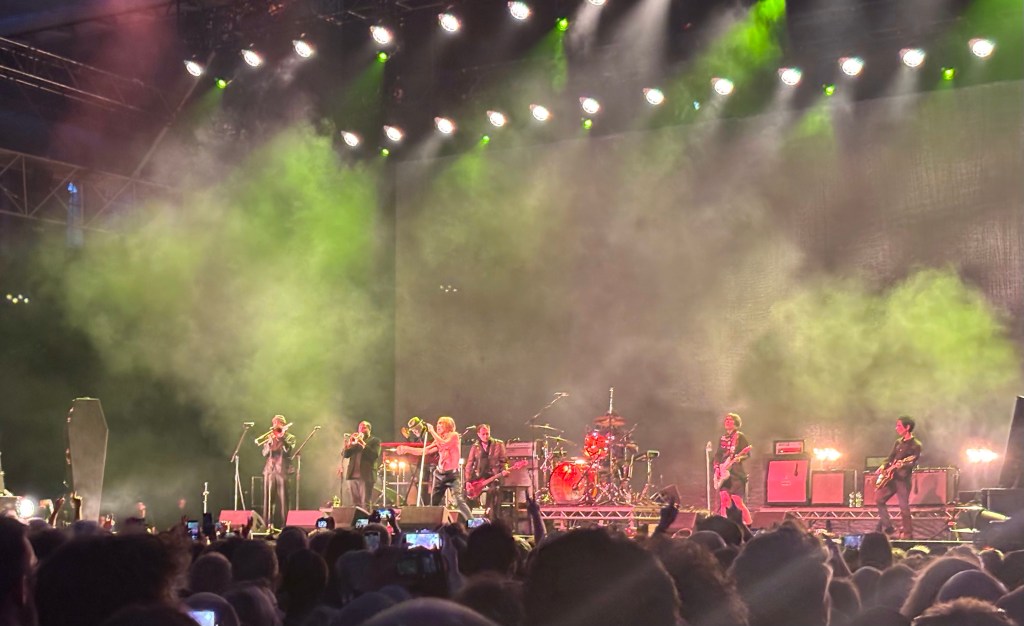

Iggy’s lust for life undimmed

Once on stage he was a wild beast. The crowd, a very broad spread of ages, greeted him as the returning hero which he is: the last survivor of the three godfathers of punk, since we lost Bowie and Reed.

-

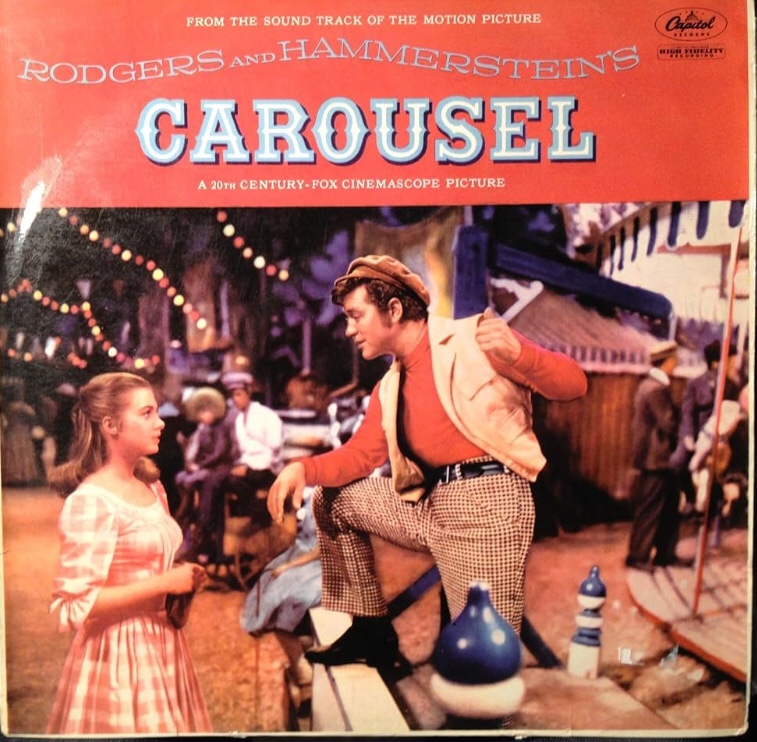

What the song meant to her

Its aching regret makes it one of the most powerful songs in musical theatre.

-

The case for Screaming Lord Sutch

Can any other British politician match his record of policy delivery?

-

George and the glis-glis wars

“Are you or your wife squeamish?” he asked. George, normally a compassionate, politely spoken and gentle man, had been pushed to the edge, as was evident from his reply.

-

John Didcock: celebrating a Watford Grammar School legend at 90

It’s quite easy to teach a good pupil. But to connect, as he did, with the more difficult ones, is something special and rare.

-

A Complete Unknown – Bob Dylan

For a hero of the peace and love generation, he sure harboured a lot of hate.

-

Chronicles of my Holiday Wanderings (1891-1901) by Harry Bond

From September 1891 until April 1901 Harry kept a meticulous record of his holidays: some by train, some by boat and some by bicycle. It is a fascinating record of a more leisurely age of tourism.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.