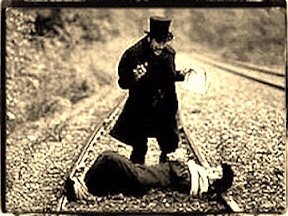

The villains were easy to spot in silent movies. They had long dark cloaks and top hats, and they laughed maniacally as they twirled their long moustaches while tying pretty girls to railway lines. (Actually, no, but still, you know what I mean. Think Dick Dastardly.)

I’d like to say that the film industry has become more sophisticated in the last century or so, but I’m not sure I can. Of course bad guy fashions change a bit, especially if there’s a war on: Native Americans, Mexicans, Germans, Japanese, Chinese, Russians…English, of course. Hollywood is obviously pitching to an audience who need a bit of help. How do we know that Indiana Jones is a good guy in Raiders of the Lost Ark? Because he’s up against the Nazis, naturally.

We English can take it. Historically we’re not an oppressed nation: Britons, it is said, never, never, never shall be slaves. And we understand that the American habit of demonising the English arises from a lingering feeling of inferiority: despite winning the War of Independence, becoming global top dog (at the time of writing) and dominating world trade and finance (at the time of writing), Americans suspect that the English are still somehow one up on them.

I’m talking about the English here, not the British. If you see a Scottish fellow in a Hollywood movie, he is probably the quirky lovable boyfriend or a heroic wild bearded and kilted clansman fighting impossible odds against the treacherous and brutal English. The only bad Scot you’ll see on screen is when the whole cast is Scottish, and the drama requires it. Note that to avoid baffling their audience, American films will only feature the softest of Scottish accents, or else give the part to a good safe American or Australian.

The Welsh, however…allow me to declare an interest. Although I was born and raised in England, have lived here all my life, have a home counties accent and generally identify as English, my father and grandfather grew up in Wales, and my DNA profile has me 66% Welsh, compared to a mere 28% English and Northwestern European. As a middle class, apparently English, straight white male I’m not a natural candidate to claim victimhood, but encouraged by this DNA result I’ll have a go: have you seen how Welsh people are portrayed in films or television, if they are portrayed at all? Wikipedia’s “List of fictional Welsh people” is pitifully small:

Of course that could be a Wikipedia problem rather than a Welsh one. Nor is this about Anthony Hopkins, whose portrayal of the murderous Hannibal “the cannibal” Lecter was resolutely English. Hollywood has provided some sentimental films (starring mostly Americans) such as How Green was My Valley. But Welshmen on film and British television are typically shown as loquacious, smarmy and untrustworthy. Perhaps Shakespeare started it with the verbose Fluellen in Henry V.

One prominent Welsh role omitted from Wikipedia’s modest list is Spike from Notting Hill, played by Rhys Ifans and scripted mostly as an idiot. Spike, like Fluellen, is undoubtedly a good guy: (spoilers) he galvanises the team into action by pointing out that Hugh Grant’s character has been a “daft prick” and bravely holds up the London traffic to ensure the success of the mandatory zany dash.

But we cannot forget the protagonist’s description of him as a “masturbating Welshman”. I can’t imagine that treatment being dished out to a Scottish character except perhaps in Trainspotting, where they’re all Scottish. The Welsh suffer from gross underrepresentation in film and TV, and when they do appear, it is usually in an unflattering light.

My second complaint arises from my modest height. Remember Shrek? The villain of the piece is Lord Farquaad: he’s certainly a nasty piece of work. But he is repeatedly mocked and short-shamed by the good guys when he clearly has no control over his height.

Farquaad is just one example of the stereotypical short, sneaky guy, characterised by actors like Danny DeVito. To be fair, this is part of a long-established tradition: over 200 years ago it suited British interests to paint Napoleon as comically small, although it seems he was of average height.

More serious, though, is the issue of disability and facial disfigurement. Again, I must declare an interest. My daughter Alice was born with a cleft lip and palate – happily, due to the care of the NHS and the skill of its surgeons, you wouldn’t see it now unless you look for it. She is weary of disfigurement being used as shorthand for evil. She grew up watching The Lion King, where the bad guy not only has a scar on his face, he is literally named after it. Alice has shared some of her feelings in response to the issue.

“The first time I saw a cleft lip on TV was Tom Burke in Casanova , and his cleft lip was noted a sign of his father’s sin, or similar. And the first time I got angry about a scar as shorthand for evil was in the 2013 Lone Ranger reboot with Johnny Depp. There was also a backlash to Roald Dahl’s The Witches (2020), with disabled communities being very disappointed in hand deformities being shown as monstrous. I suppose monstrous is a key word here, often characters with physical deformities and disabilities are shorthanded for ‘not fully human’ and therefore hateable and sometimes killable without guilt in the wider plot. This is something which definitely contributes to ableism in wider society.”

In fiction, scars and burns are usually assumed to be the just deserts for evil deeds in the past. The Joker from Batman is an exception: his unusual features were said to be the result of an accidental fall into a tank of chemical waste, which also turned him insane. Hardly his fault, then, but he’s ugly, so he must be the bad guy, right? And if you spot an albino in a film, he probably ain’t a good guy. There are plenty more examples of disability or disfigurement being used to signal villainy: Captain Hook, Voldemort (although Harry Potter did sport a rather neat scar), the Phantom of the Opera, Darth Vader and Freddy Krueger to name a few.

The highest profile and most prolific offender in the disfigurement-villainy trope has been the James Bond franchise: Blofeld, Le Chiffre, Jaws, Emilio Largo, Alec Trevelyan, Zao, Raoul Silva and counting.

In 2018, Changing Faces, the visual difference and disfigurement charity, launched a campaign called I Am Not Your Villain, to address this issue. If the producers of the Bond franchise noticed, they certainly didn’t care. They pressed on with No Time To Die, featuring Rami Malek as the disfigured villain Safin, released eventually in 2021.

For good measure, they added Dali Benssalah as Primo, an evil accomplice with a bionic eye, and Christoph Waltz as Blofeld with a prosthetic eye. No sign of any sensitivity to disfigurement issues yet.

This matters. According to research carried out by Changing Faces, people with visible differences report long-term impacts from not being represented in society and across popular culture: a third report low levels of confidence, 3 in 10 have struggled with body image and low self-esteem, and a quarter say it has affected their mental health. These people have enough to deal with without films and books constantly depicting villains as disabled or with visual differences, which encourages fear, mocking of bodily difference, and bullying, whether online or in person.

Film makers or actors should not be allowed to argue that the appearance of their villains is “in context” or necessary for characterisation. They’re just being lazy. Disability advocate Jen Campbell has written a superb takedown of the lazy evil-signalling habits inherent in the Bond films, and the damage it causes. As she says:

Where is the nuanced storytelling? Why can’t they trust audiences to recognise ‘bad guys’ without these markers? Why does a villainous backstory heavily rely on disability and why doesn’t disability and disfigurement intersect with plot in more meaningful ways, in Bond films and beyond? Besides being offensive, it’s lazy and boring.

Film makers and actors take note. Please don’t create or accept roles perpetuating negative stereotypes about disabled or facially disfigured people. It is never acceptable to insult, mock or prejudge people for characteristics they cannot control. It’s time we moved on.

Leave a comment