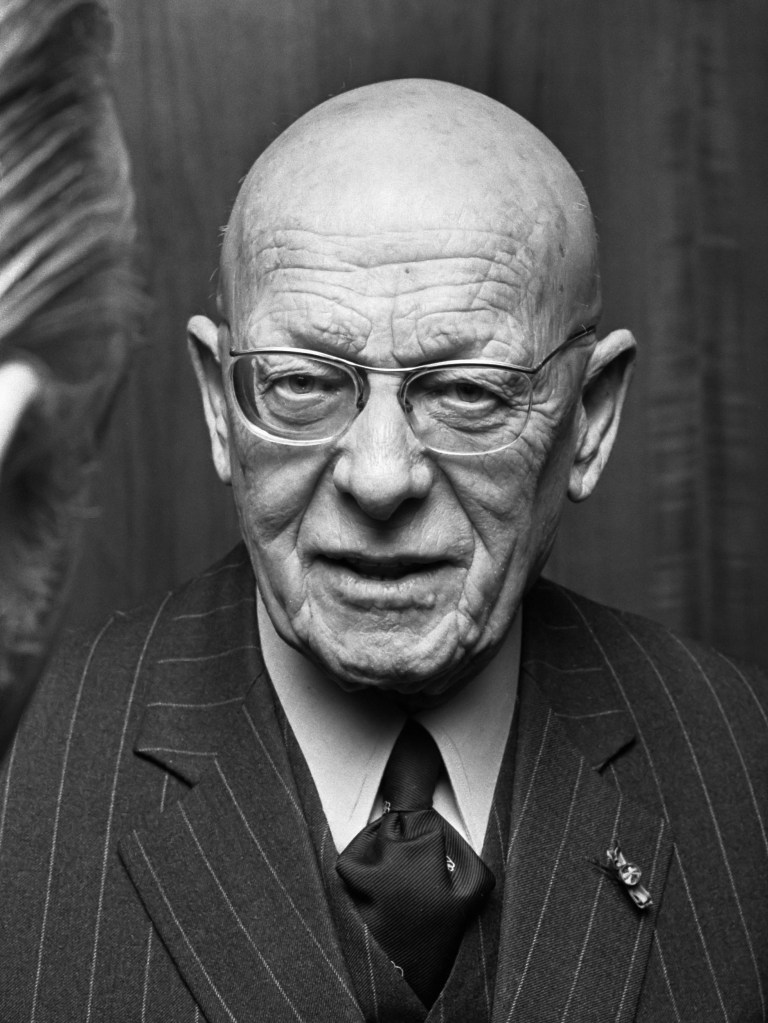

Fred Holder in 1973

During and following a career in the City in which he became Chief Investment Manager for Lloyd’s Bank, Fred Holder (1913-2009) spent 24 years as Honorary Secretary, Treasurer and Council member of the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF – now known as World Athletics) from 1960-1984, and was subsequently Honorary Life Vice President, remaining closely associated with the IAAF for about 20 further years, attending and speaking at Congresses. While in hospital in 1998, at the suggestion of his son John, he wrote down his memories of the time he spent at the highest level of athletics administration. John has now very kindly allowed me to publish these on Ramblings.

By all accounts Fred was a man of great integrity and tact, with an unshakeable sense of fair play. These qualities won him trust, respect and friendship around the world, often in countries naturally in opposition to the UK. He spent much of his time with the IAAF as their troubleshooter and ambassador, dealing with tangled political problems like the conflict between the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan, the admission of Israel to international athletics, North vs South Korea, Olympic boycotts and more.

He wrote a fascinating insider’s account of this turbulent period of in athletics history, never before made public. There is a brief summary of Fred’s life in this obituary.

Fred’s narrative is very diplomatic, and omits some of the skulduggery from his telling. His son John has told more of the story in a separate section following Fred’s account of events.

Many thanks to John Holder for allowing me to publish Fred’s story, and for the photographs and extra information he has supplied.

***************

24 YEARS IN THE IAAF by Fred Holder

In an ideal world, politics should play no part in sport. Unfortunately that is not how it is.

In the 24 years I spent in office with the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF) (1960-1984) we were constantly confronted with political problems, mainly in regard to international relations, though occasionally we had to intervene or arbitrate in domestic situations within the countries whose athletic associations were affiliated to us. Athletics being the most universal of all sports, our membership virtually covered the whole world – more countries than the United Nations or any other organisation (200+).

Some of the main conflicts involved China (the mainland and Taiwan), Germany (East and West), Korea (North and South), Israel and the neighbouring Arab states, South Africa and Zimbabwe (apartheid and other racial tensions) and USSR (over Afghanistan).

Often we had to come to the support of one of our member associations which were being subjected to interference or pressure from its own government. A commission of enquiry had been set up in the USA by Jimmy Carter’s administration to investigate alleged shortcomings in the administration of Olympic sports in that country. Evidence I gave to the Commission (and published in its reports) resulted in a major reorganization. Whereas there had been one controlling body, covering all sports from athletics to baton-twirling, with other break-away bodies, including the one controlling college athletics, it was decided to establish a new body called The Athletics Congress (TAC), which represents all Track & Field athletes in the USA, and is affiliated directly to the IAAF, and governs no other sport.

Nearer to home we had intermittent trouble over Northern Ireland. The UK governing body for athletics (which has undergone various name changes) is responsible for Great Britain & Northern Ireland. On the other hand, from time to time dissident bodies have been formed, purporting to represent All-Ireland, and sometimes succeeding in entering combined teams of athletes from the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland in competitions such as cross-country events in Belgium, which we have had to declare illegal. Mostly these ‘domestic’ disputes tended to involve Caribbean islands and Central American countries.

CHINA – Part 1

For the period of the 1939-45 war, the IAAF (up to then located in Stockholm since its inauguration in 1913) was moribund. It was revived after the war, and the HQ moved to London (largely on the initiative of Lord Burghley, later Marquis of Exeter) who was to be President of the Organising Committee for the Olympic Games in London in 1948. Many memberships had effectively lapsed. In the case of China, a body had been established in Peking to succeed the previous member for China, and was duly enrolled. However, soon there were approaches from Taiwan, where the self-styled Republic of China A.A. claimed the right to membership. The stance of the ROC government, under General Chiang Kai-shek, was of course that the ROC rightfully represented the whole of China, including the mainland.

After much debate the IAAF Congress in Melbourne 1956 during the Olympic Games, decided to admit the ROC (Taiwan) as effectively the member for that territory, alongside the People’s Republic of China Association representing the mainland. Peking promptly rejected this decision and withdrew their membership. There followed a long period when mainland China was isolated. IAAF members were forbidden from competing against non-members, they are excluded from international competitions including Olympic Games, their performance records were not officially recognised and so on.

Many approaches had been made, via various channels, to find a way out of the impasse, but Peking was not interested. Eventually it was decided at an IAAF Council Meeting held in Edinburgh (to coincide with the Tattoo) in the Spring of 1973, that I should go to Peking to try to find a solution. At first there was pressure from Umrao Singh (an Indian government minister serving on our Council) to accompany me, because of his claimed knowledge of Chinese international relations.

Fortunately the Council concluded that I should go alone. Approaches were made through diplomatic channels, and it was agreed that I should be received in Peking. Moreover it was stipulated by the Peking Government that I should not appear in any official capacity (I was Honorary General Secretary of the IAAF at the time), but simply as an individual – Mr Holder. This was quite an exciting prospect, as travellers to China were comparatively rare then. It was still the time of the Cultural Revolution and there were heavy restrictions.

I was due to be in the Philippines (Manila) in November to assist in the establishment of an Asian Amateur Athletic Association. There had been many failed attempts due to disagreements between the countries in the area, and it was felt that my experience in the setting up of the European Athletics Association in 1971 could help. I therefore arranged to combine the two trips. On leaving Manila, where we successfully established the AAAA and held the first Asian Athletics Championships, I went to Hong Kong for two days. I had to keep my Peking destination secret, and it was particularly imperative that the Taiwan delegates had no inkling of my plans – otherwise Peking would have suspected collusion.

On leaving Hong Kong (as most people in the area thought, to return to London) I crossed to the mainland and proceeded by train to Canton., where I was told I would be met. On the train journey there was a fellow traveller who turned out to be an American diplomat. At that time the USA did not have an embassy in Peking, but maintained a small diplomatic mission, whose members enjoyed the use of certain facilities at the British Embassy. I was to have no contact with our Embassy. On arrival at Canton I was duly met by an English speaking Chinese official, who explained that since there would be a five-hour interval before our plane left for Peking, he had arranged a little sight-seeing tour of Canton. At the end of the tour we arrived at the airport for a meal in a private lounge before boarding the plane. When we passed my American ‘friend’ in the departure lounge (where he had presumably spent the last 4-5 hours) he looked quite startled to see me being escorted onto the plane. Naturally I had not disclosed the purpose of my visit. On arrival in Peking I was installed in a rather basic hotel, and told the arrangements for the following day.

I was duly collected in the morning and driven to some government offices, where I found myself in a large room with many armchairs arranged in a circle and was introduced to half a dozen important looking officials, all dressed identically in the standard Chinese dress of those days (no western collars and ties). After the formal welcome (I was strictly Mr Holder with no other title), and after tea was served, the discussions began. The process was laborious, as all the Chinese officials spoke in Chinese, and every sentence was translated by the interpreters present. They spoke in calm, polite tones, but the language was harsh, even vicious at times. The Taiwan regime was referred to invariably as the ‘Chiang Kai-shek clique’.

I of course took the line that we did not in any way dispute their claim to sovereignty over Taiwan. We were merely being pragmatic in observing that under the present state of affairs, the Peking athletic organization had no possibility of organising, controlling or developing the sport of athletics on the island of Taiwan. (At that time there was spasmodic exchange of gunfire between the mainland and Taiwan). Equally we disregarded the ROC (Taiwan) claim to be the rightful Government of all-China (plainly ludicrous in practice), and therefore to represent all Chinese athletes. Our primary concern was to provide the opportunity for the sport to develop in all parts of China, and for athletes in all the territories to be able to compete internationally on equal terms.

Peking (The People’s Republic) had a rooted objection to the Government in Taiwan (and all its institutions there) assuming the title of Republic of China. I tried to explore the possibility of our recognizing Taiwan under a less contentious name (of course they would have to agree to the change), but they stuck to their hard line—no way would they countenance the recognition of a separate governing body for athletes based in Taiwan, whether we called it ROC, Taiwan, Formosa or any other name. Nor would they recognise any body (such as the IAAF) which formally recognised ‘the Chiang Kai-shek clique’, however styled. Their position would not change, they assured me, in 100 years!

All this fruitless talk lasted some hours. We had put aside three days for my visit, and we agreed to adjourn and assemble again on the following morning. As I pondered overnight I reached the conclusion that we were in a state of deadlock.

When we met the next morning, I opened by saying ‘I have no new arguments to put forward: do you have anything new to say to me?’ The response was immediate ‘’No, you have made your position clear and we have not changed our position, nor will we do so. May we suggest that we terminate the talks , and we we would like to invite you to a little sightseeing to make your visit to Peking more enjoyable.’’ We all shook hands in friendly fashion and plans were made for my tour after lunch.

I have memories of being driven down wide avenues, with very few other cars, but thousands of bicycles on all sides, passing the huge almost empty Tiananmen Square (years later the scene of the infamous student protest massacre) and visiting the Forbidden City. There I received VIP treatment and was somewhat embarrassed as Chinese visitors there to see the precious treasures were brushed aside by my escorts so that I had an unimpeded view. After a visit to the Summer Palace and other sights, I was told a banquet had been arranged in my honour that evening. There were about twenty dignitaries present (all male) and they had invited as a guest Ni Zhiqin, an athlete who had recently broken the world high jump record – though it could not be officially recognized. We were served Peking Duck (naturally!) with great ceremony on silver salvers, and there was plenty to drink.

The next day I was seen off at the airport for a flight to Paris (stopping at Karachi) and then to London (there were no direct connections with London at that time). I have two small memories about my departure.

1) I was given a copy of the ‘Little Red Book’ (Thoughts of Chairman Mao): and

2) I was approached at the security point by a pretty Chinese girl in uniform, saying “Excuse me sir, please sir, may I search your body?”

The visit to Peking cannot be claimed a success, but some contacts were made in an amicable fashion. I later met the sports officials who were present at other venues around the world, and pressure was maintained by other sports bodies including the IOC. Later the Taiwan organisation agreed to change its name to ‘Chinese Taipei’, a rather curious compromise. Eventually, in 1978 (much less than 100 years after my visit!) Peking applied to re-affiliate to the IAAF, and they were accepted, paving the way for their eventual return to the Olympic Games (though they bided their time till they felt they would make a respectable showing).

Unfortunately the IAAF Congress thereupon decided to expel Taiwan (ROC) in flagrant breach of its own constitution, in a move to appease Peking. That started another “Chinese Story”.

CHINA -Part 2

The IAAF Council reviews all major proposals for the Congress agenda, sometimes adding its own recommendations, at other times leaving the delegates to form their own views. At the 1978 Congress I was dismayed when the Council, by a majority, decided to support the proposal (I forget from which country) to expel ROC (Taiwan). There was a long debate in Congress and a two thirds majority was required. Despite an impassioned speech by Chi Cheng (the popular former multiple sprint world record holder from Taiwan) I sensed that Taiwan was going to lose.

I therefore decided to intervene. In general it is accepted that Council members do not speak in Congress in opposition to a Council motion or recommendation, but I felt that, as Honorary Secretary, I should clarify the law on the situation. Speaking from the platform, I expressed the view that Congress had no power to expel a member who had not offended against its rules. Taiwan was a member in good standing, and had committed no offence. I warned that if Taiwan was expelled, they would have a right to appeal in a court of law, and that in my view they would probably succeed. My warning was ignored and Taiwan was duly expelled.

Before long Taiwan started proceedings in the High Court in England. The case appeared in the lists as Reel v. Holder. Reel was Chi Cheng’s married name, and she represented her Association. The IAAF not being a corporate body could not be sued as such, so as the only member of the IAAF Council residing in the UK, I was named as respondent. (My friends on the Council jokingly offered to send me parcels if I ended up in prison!) To the dismay of the Council (but not to my surprise) the decision went against us. The initial reaction was to dispute the authority of the English court to adjudicate. However, after seeking advice from international lawyers in various countries, including a former judge of the International Court in the Hague, they had to accept that no other Court was competent, so they decided to lodge an appeal in the UK.

The Court of Appeal was presided over by Lord Denning, then Master of the Rolls. Leading QCs appeared on both sides, and the hearing lasted several days, with lengthy references to previous cases involving clubs and societies. Lord Denning gave a masterly summing-up, finding the case against us clearly proved, and the other two judges concurred in their own judgments. The case was fully reported in The Times and appears in the All England Law Reports, and has established an authority for similar cases occurring since then.

On our first appearance in Court together, Chi Cheng greeted me warmly as an old friend. At the end of the case, I met her with her advisers at the Savoy Hotel and congratulated them. Taiwan (under its new name of Chinese Taipei) has remained in the IAAF ever since, without problems.

Athletes from Taiwan and the mainland regularly meet in international competitions and there have been absolutely no problems. In fact in 1993 Chi Cheng accompanied a group of Taiwan athletes on a tour of mainland China, and a party of athletes from the mainland visited Taiwan.

(You can read more about the “China question” here.)

ISRAEL

Israel has been a continuous problem, never completely resolved. My first experience over Israel goes back to 1962. In that year Asian Games were staged in Indonesia – Djakarta. An IAAF permit to stage athletics events was given, subject to the normal conditions, one of which was that all countries in Asia must be invited, and there should be no hindrance to travel there. As the date of the Games approached , we heard that the Israelis were not being granted visas. We threatened that our permit would be withdrawn if our conditions were not fulfilled, with the result that any athletes taking part would become ineligible for future competitions under IAAF rules. This caused a big stir in Djakarta. The IAAF representative appointed by us – an Indian – was personally abused and threatened and we thought it prudent to withdraw him.

The Games duly went ahead without our permit (and without any Israelis). Most countries, trying to keep peace with the Indonesian organisers as well as the IAAF, opted to send ‘token’ teams, omitting any athletes likely to be needed for future international events. The only exception was DPR Korea (North Korea) who defied the IAAF ruling, resulting in some of their best athletes becoming ineligible. This had repercussions two years later at the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo. Lord Exeter, Donald Pain and I, regarded by North Korea as the villains of the piece, received threatening cables daring us to appear in Tokyo. With large numbers of North Koreans living in Japan, there could conceivably have been trouble. However, we alerted the Japanese and they provided maximum security. I never felt uneasy during my stay in Tokyo, but it was a novelty to have an armed guard stationed in the corridor near my bedroom door in the hotel.

There was never any difficulty about admitting Israel to the Olympic Games (though we cannot forget the appalling massacre in the Athletes Village at the Munich Games in 1972), but we had to fight hard on their behalf in regard to other all-Asia events and the Mediterranean Games, due to the persistent opposition of the neighbouring Arab states. A partial solution was eventually found by persuading the European Athletics Association to include Israel in their competitions. (Perhaps there is a parallel with Israel being included in the Eurovision Song Contest.)

I was involved in many of these negotiations, the most important one being when I went to Israel with Adriaan Paulen (?1973), then the European A.A. President, to try to broker a deal which would allow Israel to to have some kind of limited representation at an Asian event scheduled for Bangkok. We met the full Israeli sports establishment. They were quite intransigent, and unwilling to contemplate the slightest concession. They were also defiant in persistently inviting Jewish athletes from South Africa to compete in Israel in their Maccabiah Games, at the time when South Africa was excluded from the IAAF.

The conflict with Palestine also caused problems. For many years the IAAF maintained it could not affiliate a Palestine governing body, as there was no clearly defined independent state of Palestine. Many Palestinian athletes resided in neighbouring Arab states and competed internationally under their auspices. Eventually ‘Palestine’ was granted membership, but it was a token gesture of appeasement and they have played an insignificant part in competitions, but always send delegates to Congress.

GERMANY

The history of German athletics since the 1939-45 War closely follows the political changes which are well known, from the time of the enforced partition between the DDR (East Germany) and the FRG (West Germany). Under the communist regime of the DDR the sports organisations were state controlled and state financed. Achieving success on an international level in sport was seen as a form of propaganda to justify their system. Much has been made of alleged drug misuse in sport, and recent revelations have shown some of the accusations were justified. However, I am not convinced that the problem was vastly greater there than in many other countries. Much bad practice was imported into Europe from the USA, where controls – even to this day – have always been lax.

A more important explanation of DDR success (which was out of all proportion to the size of the population) was the highly organised system of selection and training. Children with the right physical attributes and temperaments were put into special Sports-Schule, where their academic education was not neglected, but they could be carefully developed in their sport. (I suppose that one could draw some comparison with Cathedral Choir Schools). As athletes reached competition stage, they enjoyed privileges, including of course foreign travel, but discipline was strict. (Definitely no room for ‘Gazzas’, whatever their sporting prowess). The main centre of excellence was the Leipzig Institute of Sport (they awarded me a diploma when I visited them, but not for my athletic prowess!) Similar methods were of course applied in other Communist countries, but nowhere as efficiently as in the DDR.

It is interesting to note that following the fall of the ‘Berlin Wall’, the combined strength of the united Germany has not been as great as might have been expected, though Germany is still one of the leading countries in athletics as well as other sports. Before the political reunion there were several moves, initiated from both sides, aimed at producing an All-Germany team, or direct contests between the two sides. A few such meetings took place on neutral ground – in Denmark or Sweden – but they had no official recognition. At Congresses it was clear that the DDR always slavishly followed the Communist line dictated by the USSR. On a personal level there was no animosity between either officials or athletes of East and West – they still all regarded themselves primarily as Germans.

KOREA

There was a vast difference between North Korea and South Korea. The administration of sport in Seoul was democratic, receiving a good deal of support from business sources. At the Asian Continental level they were quite active, and in fact staged the second Asian Championships there, which I attended, in 1975. At that time they were already considering making a bid to stage the Olympic Games, and I toured some of the facilities. They had already staged a World Championships in shooting and – by invitation – I fired a few rounds with rifle and pistol. The score was not recorded.

In North Korea the sport was of course state-controlled, but not well organised. At congresses they were always politically motivated, and disputed the right of South Korea to be independent. During one of my visits to Korea I was taken to Pyongyang, and surveyed the no-mans land between the opposing armies, and the place where a secret tunnel under construction by N.K. had been discovered.

One of the troubles in dealing with Korea is that every second person is named Lee. Once during a Congress in Stockholm, my wife reported that ‘a Korean’ was waiting outside our bedroom and wanted to have a private talk with me. Thinking it would not be diplomatic to ask him if he was ‘North’ or ‘South’ (DPRK or RoK), I said “Ask him his name”. The answer of course came back ‘Mr Lee’.

USSR

The Soviet Union was the most powerful nation in athletics, in every sense. The combined strength of its Men’s and Women’s teams put them at the top, and of course their political influence was immense. Apart from the recognised Communist Bloc, many small countries in Africa and elsewhere, which received aid in various forms from the USSR, slavishly followed their masters in Congress. Over the years I got to know many of their leaders well.

In the early years I had to listen to many angry speeches by Leonid Khomenkov. He spoke no English and understood hardly any, and seemed a difficult character. However over the years perhaps he mellowed somewhat, or perhaps I just got to know his character better. Anyway we became friends, and he was often a good ally on the Council. Once he came to stay overnight with us at our house, Brookhurst Grange, accompanied by his young interpreter at that time, Yuri Markov. This was when Russian visitors to London on official business were not allowed to stray further afield without specific permission from their Embassy, so we had to smuggle them out.

We called briefly at my son’s house, Elm Lodge, and he expressed surprise that a young man should have such a house for the exclusive use of his own family – though he seemed to take it for granted that I should have a large house due to my elevated status in world sport (!!). After all, even he had a country dacha in addition to his town house. His day-job was Head of the Moscow Institute of Sport, and like all such officials, he was a ‘Professor’. We discovered that we were almost exactly the same age, and in later years regularly exchanged birthday presents of vodka and whisky. Sadly he died in 1997. One of his later interpreters, reporting on his illness or indisposition towards the end thought he had declined because his life had become so empty when he retired from the IAAF in 1992. His place on the Council was taken by Igor Ter-Ovanesyan, former champion long-jumper and great rival of Lynn Davies, who won the 1964 Olympic long jump in Tokyo. He speaks English fluently and always asks after Lynn when we meet.

Yuri Markov was an interesting young man. As a young orphan he was placed in the Russian Naval school, and eventually into the Navy. While he was there he took the opportunity to study languages and his knowledge of English was good, although he had never been abroad until he was allowed to accompany Khomenkov to Council meetings, and he was clearly fascinated by the new world he was discovering. Eventually he progressed to be full-time General Secretary of the International Boxing Association.

Another Russian I got to know well was Vladimir Rodichenko, a member of the IAAF Technical Committee. By profession he was a civil engineer, specialising in the construction of gas production plants. He also visited Brookhurst Grange. I took him to a village cricket match – I think at Coldharbour where they hold a festival cricket week – the first cricket he had seen, and we had a drink in the beer tent. Somewhere at home I have a book on athletics written by him (in Russian of course) and he drew my attention to a section where my name was mentioned a few times. At that time I could recognise my name in the Russian script. On one visit to Russia I gave him Peter Ustinov’s autobiography, in English, which he was anxious to read.

Later there was a time when he fell out of favour with the Soviet authorities, and had a few years in the wilderness after I retired from the IAAF in 1984. I never heard the reason – he doesn’t talk about it and he has since come back in favour. He had been appointed to lead a team of three Technical Delegates for the first World Junior Championships in Athens (1986); although I was no longer in the IAAF (except as an Honorary Life Vice-President) Primo Nebiolo appealed to

me to take his place, which I did.

Returning to political issues, one is bound to recall the Olympic Games in 1980. The USSR first applied to hold the 1976 Games: I was present at the IOC session which awarded the Games to Montreal. There was bitter rivalry between Los Angeles and Moscow, and Montreal were the outsiders. On the first count Moscow were in the lead, but did not achieve an overall majority; in the second round most LA votes were transferred to Montreal, who duly won. Politics certainly played a part in this.

As we approached the 1980 Games a crisis developed over the invasion of Afghanistan. Many countries decided to boycott the Games in protest, including the USA. The UK left the final decision to the British Olympic Association, who decided it was in the athletes best interests to take part. The IAAF and the other International Sports Federations decided to go ahead. The IAAF also held its biennial Congress at the same time in Moscow, and most countries were represented – including the USA, despite their boycott of the Games.

Artur Takac (who speaks Russian as well as several other languages) and I were the Technical Delegates, charged with supervising the organisation and conduct of the athletic events. We had an excellent working partnership with our Russian colleagues, whom we knew well through a number of visits to Moscow before the Games. There was intense media interest – mostly not concerned with athletics as such, or any other sport, but looking for newsworthy political angles.

I gave a number of interviews, including Des Lynam for the BBC, Adrian Metcalfe for Channel 4 and the most serious one (and fairly reported, I was told later), with John Simpson the BBC foreign correspondent, who still appears as a commentator on events such as Yugoslavia. Also I had to give interviews to many foreign media people from Australia, Canada and some European countries. I saw a recording of my talk to East German correspondents, speaking in English with a German voice-over. Mostly these people were trying to put down the Russians, exaggerating difficulties, stirring up complaints, accusations of cheating and so on.

My wife Beatrice was with me in Moscow, and family and friends at home were amused by a front-page headline and story in the News of the World (I think it read “Buxom Beatrice Busts Olympic Scanner”) and referred to her being checked by security guards at the entrance to one of the official hotels. Security was quite tight, but no more than necessary. A personal happy memory was being able to present gold medals to Sebastian Coe and Steve Ovett.

On one occasion we had an amusing experience in Moscow. Along with Adriaan Paulen (then IAAF President) we were invited to meet a very high-ranking member of the government, accompanied by the leaders of the USSR Athletic Federation. During some casual chat about international sport, I asked him if he thought it right and proper that the USSR should have the same power over our decisions as a small island in the Pacific Ocean. “Of course not”, he retorted, “an elephant is not a mouse!” It was mischievous of me to ask the question, as the USSR delegation had been campaigning in Congress to end the differential system of voting according to all-round achievement, participation and development- which gave more votes to Finland than to India. Their campaign on the basis of one vote per member was eventually adopted, but it was a cynical approach, because they knew that they could ‘buy’ the votes of small countries favouring their political regime (and Primo Nebiolo found he could exert influence by other means to gain the support of small countries).

A consequence of the USA boycott of the Moscow games was that the USSR decided to boycott the Los Angeles games of 1984, along with some of their communist supporters.

To finish with Russia and the USSR, I can recall many interesting visits in and around Moscow, in Leningrad, Donetsk and Odessa, boat trips and picnics on the Moskva river and the Black Sea, with privileged access to many interesting places with our Russian friends as guides. At one time they were anxious to arrange a wild bear hunt for Lord Exeter (which they thought would be more his ‘cup of tea’) but I don’t think it ever materialised. My wife came with me on the night train from Moscow to Leningrad on one occasion.

SOUTH AFRICA

South Africa’s virtual exclusion from sport on the international level is common knowledge. For many years we kept the South Africa Athletic Association in membership of the IAAF, on the grounds that as an association they had an ‘open’ policy without racial discrimination, and their officials had openly opposed the government stance. However, the rest of Africa wanted them out and they were eventually expelled, and only recently re-admitted on the change of government. I felt sorry for those athletes who were denied competition (black and white) through no fault of their own. During the difficult years I was several times invited to South Africa to ‘see for myself’ that there was no discrimination within the sport, but Lord Exeter and I decided that it would be wrongly interpreted and severely criticised by many IAAF member countries if we went (being President and Hon Secretary then) although some other Council members and officials from several countries did pay visits, and were duly entertained as well as informed! In practice it was very difficult to develop the sport in a multi-racial manner so long as children were segregated in schools.

In the Montreal Games 1976 we had boycotts by some of the African and Caribbean countries, as a protest against New Zealand, who had sent an All-Blacks rugby team to South Africa.

The Rhodesia team (now Zimbabwe), which had arrived in Munich in 1972 were forced to go home, following protest and threats by other African countries against the political regime in Rhodesia at that time.

© Frederick Holder 1998

***************

My father Fred Holder, by John Holder

Fred Holder’s introduction to Athletics Administration

Fred was a decent club athlete: he ran cross-country, captained Lloyds Bank Athletic Club, and was a member of South London Harriers. But his active athletics career was ended by a slipped disc, so he went on a course at Loughborough University and qualified as a middle-distance coach. He also regularly acted as announcer at Sports Day at the Lloyds Bank ground in Beckenham, besides helping to organise the event. Then he progressed to announcing at the Inter-Banks Championships and matches such as Banks v Insurance Companies, and then many other events at the White City Stadium, such as the AAA Championships and Internationals. At several of these he shared announcing duties with Ross and Norris McWhirter (of Guinness Book of Records fame), who fed him with statistics.

As a schoolboy I attended most of these competitions and particularly remember an evening London v. Moscow meet in 1954 when Chris Chataway narrowly beat Vladimir Kuts over 5000 metres in a world record time in front of a 40,000 crowd.

Early years at the IAAF

By 1960 the existing Honorary Secretary-Treasurer of the International Amateur Athletic Association (IAAF), Donald Pain, was starting to suffer from ill health and the Marquess of Exeter, the IAAF President, wished to ensure that the organisation remained based in the UK. He therefore made soundings with a view to finding a suitable British successor, someone who was involved in the sport but also had the administrative experience and financial acumen and contacts for the role. Pain himself, being another banker and member of South London Harriers recommended Fred and Lord Exeter met him and approved his appointment as Hon. Assistant Secretary.

When Pain eventually retired in 1969, Fred was unanimously elected to take over by the IAAF Council, and the office remained in London, at that time in Victoria Street. Fred then moved the office to Putney, which was cheaper and nearer to our home in Barnes, before relocating to a small office near Harrods in Knightsbridge at the request of the next President.

Fred and Lord (David) Exeter got on very well. In 1967 Fred and his wife received an invitation to the wedding of Exeter’s daughter Lady Victoria. Victoria appeared as an expert on Antiques Roadshow for many years and on her father’s death became custodian of the family estate, Burghley House, near Stamford in Lincolnshire. Fred visited Burghley on a number of occasions.

Chariots of Fire

Exeter was one of the leading characters (portrayed by Nigel Havers) in the film Chariots of Fire, and as Lord Burghley he won a gold medal over 400m hurdles in record time at the 1928 Olympic Games. Fred was also friendly for many years with another star of that film, Harold Abrahams, who won the gold medal for 100m in the 1924 Olympics. He later wrote on athletics for the Sunday Times. Abrahams came to stay the night at Fred’s house, Brookhurst Grange, and he entertained Fred at his club, the Garrick. We played the Vangelis film theme at the end of Fred’s funeral.

The Adriaan Paulen years

In 1976 David Exeter decided to retire from the Presidency, confident that he was leaving the organisation in good hands. His natural successor was Adriaan Paulen, a former Olympic athlete, a war hero (he was knighted and awarded the Dutch equivalent of the Victoria Cross), a mining engineer, who was President of the European Athletics Association. He was honourable and committed to the sport. Fred supported his nomination, but some influential Council members thought that someone should stand against him so that there could be a genuine election.

Fred was persuaded to stand, but did not campaign and was surprised to receive nearly 100 votes – over a quarter of the total. Furthermore, many members approached him afterwards to apologise for not voting for him, explaining that they had voted for Paulen because, at 73, he was ten years older than Fred, so it would be his last chance. Fred was clearly President-in-waiting when Paulen’s five year term came to an end, but nobody had counted on a Machiavellian Italian called Primo Nebiolo – of whom more later.

Fred and Paulen worked well together during Paulen’s term, which covered a difficult period during which athletics started to transition from a strictly amateur sport, as big money started to flow into sports from the growth of television coverage. In the UK a former policeman Andy Norman, who began to promote meetings and act as agent for athletes, was rumoured to be responsible for the passing of brown envelopes to competitors or their families. Clearly it was necessary to adapt to discourage such illicit payments.

Fred and Paulen recognised the opportunities presented in the new era. Fred hired West Nally, a sports media consultancy co-founded by BBC sports presenter Peter West, to advise on marketing Athletics and negotiating with television companies. Fred and Paulen also instituted the first World Cup inter-continental competition, and made plans for the first World Championships, to be held between Olympic Games.

Anticipating the growth in revenues, Fred negotiated with the Inland Revenue to gain exemption for the organisation from UK income taxes. He was also proud of having established a coaching scheme for less-developed countries.

Paulen was a strong man with clear views, but always put the interests of his sport first. He and Fred kept their expenses low, usually travelling in economy class. Paulen insisting on taking public transport from Heathrow to London, rather than a taxi.

Due to the significant expansion of IAAF activities, Fred decided to take early retirement from the bank in order to devote more time to his duties. He also won approval from the IAAF Council to create a new post of Secretary, who would be an employee, paid to carry out the Council’s decisions. He advertised the job, held interviews and hired John Holt, a former Oxford athletics Blue. John was not a Council member, but attended Council and Congress meetings. Fred continued as Honorary Treasurer. Total office staff remained minimal, with no more than half a dozen employees, even after another move from Putney to modest premises in Knightsbridge.

Primo Nebiolo

As the end of Paulen’s term approached, Primo Nebiolo, an Italian Council member, surprised everyone by throwing his hat into the ring. By covert lobbying he won a nomination to stand for the Presidency. He then identified members’ weak spots in order to win their votes, bribing people shamelessly. For some it was sufficient to promise a job that he knew they wanted (e.g. president of a regional association), for others he offered financial incentives. Importantly he promised to change the voting structure of the organisation. Hitherto a two tier system had applied, with the top athletics nations commanding the most votes in Congress.

Nebiolo promised that, if elected, he would introduce a system giving one vote to each member country. This was significant since, in Africa in particular, there were many countries whose athletes rarely, if ever, competed internationally. Nebiolo further promised that each country’s representative (plus wife – or wives) would receive an expenses paid invitation to attend all Congress meetings. Most representatives were political appointees rather than genuine athletics administrators.

In Fred’s case, knowing that he was incorruptible, Nebiolo resorted to threats. He made it clear that he knew where Fred lived, and said that his family or property would suffer if he stood against him. Having already suspected that Mafia connections had been the source of PN’s wealth, Fred was not prepared to take the risk, so Nebiolo was elected unopposed. Not surprisingly, he was never challenged in subsequent elections and died in office in 1999.

Fred was deeply unhappy about the autocratic way Nebiolo ran the IAAF, never allowing a vote if he feared he might be defeated. Nebiolo was always more concerned with self-aggrandisement than the welfare of athletes. It did not take him long to move the office from its modest London premises to palatial accommodation in Monte Carlo. He also wasted no time in publishing a glossy book, highlighting his own achievements and re-writing history. He greatly expanded the staff from six to over sixty, and travelled everywhere first class, accompanied by his entourage.

To a limited extent Fred benefited from his largesse, since each time he visited Rome he was treated as a VIP, bypassing the normal airport checks and being transported by limousine to his hotel accompanied by a police motor cycle escort. He (and his wife) were presented to the Pope on more than one occasion, at both the Vatican and Castel Gandolfo, the Pope’s summer residence.

Mostly, however, Fred and Nebiolo were at loggerheads. On doping Fred (who sat on the medical commission) thought Nebiolo was far too soft on those found guilty. In general Fred was in favour of a life ban, whereas Nebiolo was reluctant to support anything more than a two year suspension. He was also overly concerned about image. On one particular occasion an American runner tested positive after his victory in a semi-final. Nebiolo argued against his immediate disqualification on the grounds of the adverse publicity it would cause. Fred was certain that the athlete should not be allowed to compete in the final. Apart from anything else, another athlete would be deprived of a place in the final. A row ensued, but fortunately Fred was Chairman of the Jury of Appeal and his view prevailed.

On another occasion, an Italian athlete called Giovanni Evangelisti was originally awarded a bronze medal in the Long Jump at the 1987 World Athletics Championships in Rome. This was blatant cheating as the Italian official was proved to have recorded a leap longer than the actual jump. Yet Nebiolo refused to censure his assistant, Luciano Barra, who collaborated in the deceit – perhaps because it was his own idea.

Nebiolo invariably bowed to commercial pressure. Indeed, he was thought to be in the pocket of Horst Dassler (of the Adidas family) from before his election as President.

(Fred was highly embarrassed when he discovered that his wife had accepted a gift of running shoes or trainers for my sister and me from one of the Dasslers, and made her promise that she would never do so again.)

Nebiolo was also prepared to time events primarily to suit US television schedules, even insisting on the Marathon being run at the heat of the day.

Fred became increasingly despairing, feeling that he could not rein in Nebiolo and did not want to be associated with the direction in which the sport was being led. Accordingly, in 1984 shortly after the Los Angeles Olympic Games, he tendered his resignation as Treasurer and left the Council. It is also fair to say that at the age of 71 he thought that it was about time to stand down, since throughout his life he had taken the view that too many directors and executives stayed in office too long.

Some years after standing down, Fred upset Nebiolo with a letter published in Athletics Weekly, criticising the unnecessary proliferation of expensive world events. This earned Fred a long letter from the IAAF secretary stating that it was not appropriate for former executives to criticise the policies of current officers.

Although no longer in an executive role, he continued to attend all congresses and major meetings, as he was made a Life Vice-President of the IAAF and contributed to debates. Indeed, as late as 2001, when the organisation voted to change its name, (it is now World Athletics) his amendment was adopted, substituting Athletics for Athletic. His mind was still sharp until he was well into his nineties.

Lack of official recognition

Fred was a brilliant unpaid ambassador for this country and was respected throughout the world for his ability and impartiality. In my opinion it is an indictment of the British honours system that he should have been awarded nothing more than an OBE. Indeed the leaders of World athletics were shocked to hear that Arthur Gold, President of the British Amateur Athletics Board, had been knighted in 1984 (having been awarded the CBE in 1974). No-one could understand why Fred, who ranked far higher in the World Athletics hierarchy, had never been so honoured.

The Presidents of all the Regional Federations (Asian, South American etc) decided, unprompted by Fred, to lobby the British Government on his behalf. I have seen letters making representations in the strongest terms. The letters had no effect. This may have been because the proper channels were not used (I think some were addressed to Margaret Thatcher) or perhaps the powers that be objected to the interference of foreigners.

Most likely, though, the people who made these decisions were simply not aware of Fred. He was a modest man and did not court publicity.

Olympic Games

Fred was never a member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), but he was closely involved with the Games over many years. The main function of the IOC was to decide which City should host the Games and which sports should be included. Once the City had been chosen from the applicants, the games were organised by the governing bodies of the individual sports. Prior to drawing up a short list of potential host cities, the IOC would seek the views of the IAAF and others regarding suitability. In 1980 Fred was awarded the Silver Medal of the Olympic Order.

I think Fred attended at least twelve Olympic Games, but he had a pivotal role in six of them as a technical delegate for track and field athletics. Normally a city would be appointed six years before the Games, and it would be the job of the technical delegate(s) for each sport to liaise with the City’s organising committee to ensure that due preparations were made in accordance with international rules. It would be their responsibility to ensure that the stadium was built in time, that the track was the right dimensions, that accurate timing was provided, that officials were properly trained, that adequate provision was made for worldwide press and the media, and so on. In the years before the Games he would visit the host city on several occasions, culminating in attending a ‘rehearsal’ event to make sure everything went smoothly. In fact, he had become so indispensable in this role that, after he resigned, he was asked to help out with the next Games in Seoul and write a manual for successors.

Olympic Games snippets

I happened to be at my parents’ house, Brookhurst Grange, one day in 1972 when Fred received a call from Lord Killanin, who had just been appointed President of the IOC. He wanted to pick Fred’s brains about what to expect and how to deal with the various international sporting bodies, confessing that he was a ‘new boy to all this’.

It was routine for a member of the IAAF Council to present the medals at Games. If there was a Council member from the same country as the winner, it was standard practice for him to be given the opportunity of presenting the medals for that event. Accordingly Fred presented gold medals to many famous British athletes such as Daley Thompson and Sebastian Coe. You can often see the back of his head in old news clips!

For several Games, Fred was a member (sometimes Chairman) of the Jury of Appeal, which was the final arbiter for disputes over disqualifications etc. The Jury had access to video recordings and could take evidence from the parties involved. Jury members were fitted with jackets in lurid colours to make them stand out, and in recent years I have had fun wearing Fred’s jackets on appropriate occasions.

During the Moscow Olympics, my mother Beatrice featured in stories in the British tabloid press. When visiting the hotel where the British delegation was staying, she set off a bleep at the security check on the door and was taken into a cubicle for examination. Unfortunately Marea Hartman, the British Ladies team manager, mentioned this to a journalist and next day the News of the World proclaimed “Buxom Beatrice Busts Olympic Scanner”, while another paper went with “Storm in a D Cup”.

Commemorative medals were produced for limited distribution to mark all major Championships, including the Olympic Games. I still have Fred’s large collection.

One of Fred’s duties as a Council member was to ratify world records. It was necessary to meet a number of conditions. The performance had to be set at an advertised event held under IAAF rules. No in-event coaching was allowed, nor was pacemaking (properly ruling out Roger Bannister’s Iffley Road four-minute mile). For certain events there were limits to the permissible following wind and so on.

Over the years Fred got to know most Council members well and became friends with many. At Christmas time he would receive greetings cards from all over the world, often accompanied by personal letters and family photographs. In contrast to most British athletics officials, who were usually grass-roots club athletes, representatives of other countries were often political appointments or were distinguished in other fields. One of the Scandinavian members was a cabinet minister, the Brazilian was an army General (his wife was a well-known artist who gifted some of her work to my mother), the South Korean was boss of a huge construction company with major contracts in the Middle East, and so on. Fred holidayed with the Australian, who owned a boat and took him up in his light aircraft. Chi-Cheng, an elegant Taiwanese lady and former World record holder visited us at my house Elm Lodge, as did the Russian.

Fred maintained good relationships with the leaders of several other international federations and discussed matters of common interest. His friendship with Thomas Keller, the Swiss President of the World Rowing Federation proved valuable when his grandson Andrew was seeking membership of the Stewards’ Enclosure at Henley, when Keller wrote supporting his application.

As Head of the Commonwealth, Queen Elizabeth liked to attend and open the Commonwealth Games. Although the athletics competitions were not an official IAAF event, Fred liked to attend whenever he could. Usually he was the most senior representative of world athletics present and, as such, would be seated next to the Queen. We have photographs of my parents next to the Queen and Prince Philip in Brisbane and, I think, in Edmonton Canada.

Such was Fred’s discretion that the Queen felt able to entrust him with some interesting remarks for which the tabloid press might have paid handsomely. When Fred was presented with his OBE at Buckingham Palace in 1981, he was greeted warmly by the Queen.

Princess Anne competed in the Montreal Olympics and later became President of the International Equestrian Federation and a member of the IOC. Fred met her on many occasions and was a fan of her ‘no nonsense’ approach. Indeed he told the story of a reception at a British Embassy somewhere, when the ambassador went to introduce Fred to her. She interrupted saying “no need- Fred and I are old friends”. But when she was asked if she would like to meet the IAAF President, Primo Nebiolo, she declined stating that she had “no desire to meet that oily little man ever again”.

Another long-standing IOC member was Grand Duke Jean of Luxembourg. He was a keen sportsman and headed his country’s Olympic Committee and several sports federations. He had been educated at Ampleforth College and Sandhurst and had served during the war in the British army. Fred always enjoyed his company and knew him as ‘Johnny’ Luxembourg.

Marc Hodler was President of the International Ski Federation for over 40 years and was also a senior member of the IOC. A Swiss lawyer and international bridge player, he invited Fred as his guest to attend the Winter Olympics.

In Japan, Fred had the honour of escorting Princess Chichibu, a member of the Japanese Imperial Family. He found this easier than he expected, as she spoke good English. She was actually born in England and lived for a while in the US, as her father was Japanese Ambassador to both GB and US. She later married the son of Empress Teimei. Fred was conscious that few Japanese people had ever met a member of their royal family.

I have photos of Fred being presented to two different Popes. I also have a large photograph of the notorious Imelda Marcos presenting something to Fred at a ceremony in Manila. Another official photograph shows my parents being presented to the Prime Minister of South Korea.

The Japanese and other far Eastern nationalities were great present givers. Sometimes this was embarrassing. On one occasion in Taiwan the hosts discovered that it was my mother’s birthday. When they returned to their hotel room shortly before departing, my parents found a massive plate with her photo projected onto it, with a heavy ornate frame and a brass plate inscribed to mark the occasion. Although they could never see themselves displaying the gift, they could hardly leave it in the hotel room without causing offence, so took it with them, paying a huge excess baggage charge at the airport.

© John Holder 2025

Leave a reply to obbverse Cancel reply