Tim Hardin had a short and troubled life, but he left us with some exquisite songs. His reputation rests entirely on two albums, imaginatively titled Tim Hardin (1966) and Tim Hardin 2 (1967). His songs are low-energy and very short – some less than two minutes. Will Sheff from Okkervil River put it well: “There is something very disarming about how simple those songs are…a Tim Hardin song never outstays its welcome. It’s very short and pretty: one verse, one chorus, second verse, the song is over and he’s out of there. It’s like a tiny, perfectly cut gem.”

Hardin was socially awkward, and given to extreme melancholy. “People understand me through my songs,” he told Disc and Music Echo in 1968. “It is my one way to communicate.”

He was born James Timothy Hardin on December 23, 1941, in Eugene, Oregon. Both parents were musical: his mother played violin in the Portland Symphony Orchestra, and his father had played bass in jazz bands

As a child Hardin taught himself to play the piano and guitar. After completing high school, he briefly attended the University of Oregon but dropped out at the age of 18 to enlist in the Marines. He is said to have discovered heroin while posted in Southeast Asia.

After his discharge he moved to New York City in 1961, where he briefly attended the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, but found it too much like school, and was excluded for poor attendance. He started performing around Greenwich Village, playing folk and blues numbers and gaining attention for his heartfelt performances and poignant songwriting. He became friends with Mama Cass Elliott and with John Sebastian of The Lovin’ Spoonful.

A 1964 recording contract with Columbia Records was terminated with no material being released, and it wasn’t until 1966 that his first album, Tim Hardin 1 was released on Verve Records. Hardin wasn’t happy with the finished product: some demos had ended up on the final recording, and after the main recording sessions were completed, string arrangements had been overdubbed on to some of the tracks without his consent. Hardin said he was so upset that he cried when he first heard the recordings. Perhaps he shouldn’t have been surprised by the overdubbing: only recently some studio tinkering on the single on The Sound of Silence had turned Simon and Garfunkel from cult folk artists to huge pop stars. Hardin’s first album was not commercially successful, but included some of his best-known songs, such as Reason to Believe.

Reason to Believe has been covered by Bobby Darin, Peter, Paul and Mary, Glen Campbell, Peggy Lee, and the Carpenters, but in the UK most famously by Rod Stewart. It started life as the A-side of Stewart’s 1971 single, before the B-side Maggie May overtook it and the record was flipped to become a UK and US number one.

Don’t Make Promises is poignant as Hardin’s personal life was chaotic: he habitually made promises he couldn’t keep, in his personal and professional lives. It was covered by American garage band the Beau Brummels, Marianne Faithfull, Rick Nelson, Cliff Richard(!), Gary Puckett and the Union Gap, Three Dog Night, Helen Reddy, Joan Baez and Paul Weller. Radio presenter and writer Charlie Gillett said the song achieved “the elusive balance between personal miseries and universal sufferings”.

Hardin’s UK “hit” was the haunting and poignant Hang on to a Dream – it made no. 50 in the singles chart for one week. Again, it has been very widely covered, by Fleetwood Mac, Emerson, Lake and Palmer, The Moody Blues, and French rock star Johnny Hallyday even recorded it as Je m’accroche a mon reve. Hang on to a Dream perfectly illustrates how Hardin at his best could distil his personal difficulties into a song with universal resonance.

Bob Dylan reportedly said Hardin was “the greatest living songwriter” after hearing his first album. Hardin recalled: “Yeah, I played him part of the album one night and he started flipping out, you know. Man, he got down on his knees in front of me and said: Don’t change your singing style and don’t bleep a blop….”

Writer Brian Millar concluded that “Dylan was right: for some years Tim Hardin was the greatest songwriter alive. And just as no one sang Dylan like Dylan, no one sings Hardin like Hardin.”

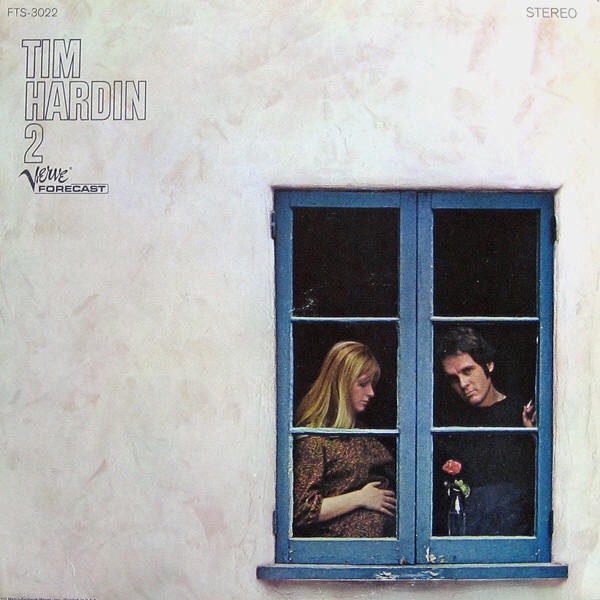

Hardin released Tim Hardin 2 in 1967: containing another batch of classic songs. If I Were a Carpenter became Hardin’s best known song when Bobby Darin recorded it, reaching no.8 in the US and no.9 in the UK. It was also covered by the Four Tops who took it to no.7 in the UK charts, and by Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash with June Carter, Joan Baez, Robert Plant, Johnny Hallyday (again), Bob Seger, Leon Russell, Willy Nelson and Dolly Parton. The Small Faces also recorded a raucous soulful live version which could not be more different from Hardin’s original – with added audience screams.

Tim Hardin’s Red Balloon is not the “Callow La Vita” song you might remember by the Dave Clark Five. This one was again covered by the Small Faces – anticipating Rod Stewart’s version of Reason to Believe with a later incarnation of the Faces.

Black Sheep Boy has been recorded by Scott Walker, Don McLean and Paul Weller. Another little gem, which will take just 1 minute 53 seconds of your time.

Baby Close Its Eyes is a gentle tender song – for once, a celebration – inspired by the birth of his son Damion in February 1967. It has been covered by Jackie de Shannon and Rick Nelson.

Hank Williams was an unfortunate choice of role model for Hardin, given that Williams died of a combination of violence, alcohol and drugs. But like Williams, Hardin had the gift of turning personal unhappiness into something beautiful. Tribute to Hank Williams, describes the last night of Hank Williams’s life, foreshadowing Hardin’s own tragically early death.

In 1965 Hardin had met the love of his life, his muse and – for as long as she could put up with him, his partner, Susan Morss. He adapted her name to Susan Moore for the beautiful Lady Came from Baltimore. He took another licence in the song: she didn’t come from Baltimore, but from Vermont and New Jersey. But it’s true to life in some ways: her Daddy really didn’t approve, and was perhaps not wrong in thinking that Hardin was, initially at least, looking for a rich girl to fund his drug habit. The lyrics are lazy: he has the nerve to ”rhyme” law with law and love with love. But it doesn’t seem to matter: it’s somehow perfect.

By 1967 following critical acclaim for his first two albums Hardin was in demand to tour Europe and the United States and his songs were being widely covered. But his work declined, due to his combativeness in the studio, his addiction to heroin, his drinking problems, and his frustration over his lack of commercial success. He began to miss shows and perform poorly, and once fell asleep on stage at the Royal Albert Hall in 1968. At the time he was seen – perhaps generously – as enigmatic. One reviewer wrote that “while his position as one of the best songwriters of his generation is unquestioned, he courted the scene in the most fumbling manner imaginable.” The writer noted Hardin’s ambivalent relationship with his audience, often ignoring them, just singing “at times badly, at times beautifully…somehow always fascinating.”

In 1969, Hardin again signed with Columbia and had one of his few commercial successes, when he returned the compliment to Bobby Darin by covering Darin’s song Simple Song of Freedom and reached the US and Canadian Top 50. But he didn’t tour to promote it or capitalise on this success: he was in no fit state.

He was asked at short notice to open the Woodstock Festival in 1969, but stage fright got the better of him, and Richie Havens seized the opportunity instead. He did appear on stage eventually, but he was clearly stoned, and his footage never made it to the album or the film.

Over the next ten years Hardin moved between Britain and the US. Late in 1969 he arrived in England to take a programme for heroin addiction but this was unsuccessful and he became addicted to the barbiturates used during the withdrawal stage from heroin. Drugs had taken control of his life by the time his last album, Nine, was released in 1973.

Leonard Cohen, when asked in a 1972 Melody Maker interview about Hardin’s cover of Bird on the Wire memorably responded “Well, Tim Hardin! Well, I think that man’s even more miserable than me.” Hardin gives the song a bluesy Joe Cocker feel.

In late November 1975, bizarrely Hardin performed as guest lead vocalist with the German experimental rock band Can, for two UK concerts – at Hatfield Polytechnic and at Drury Lane Theatre. Allegedly there was a huge argument between Hardin and Can after the London concert, during which Hardin threw a television set through a car’s windshield.

Hardin died at the age of 39 of an accidental heroin overdose in his Hollywood apartment on 29th December 1980. His obituary in the Los Angeles Weekly concluded “I don’t think Tim Hardin was ever really sure how good he was, and he rocketed from arrogance to despair conscious of the promises he couldn’t keep. He is gone, but the songs aren’t, and they will last.”

Leave a reply to robedwards53 Cancel reply