When Rishi Sunak announced the general election in Downing Street, a sodden turkey voting for an early Christmas, he set the tone for his catastrophic campaign and energised opposition parties. At last we could do something to get rid of this awful government. Sunak warned that we shouldn’t “risk going back to square one”. Risk? Square one would be progress after the last five Prime Ministers.

***************

My mother lied to the US immigration service when she went to the USA with my father in the 1980s to attend the Metropolitan Opera in New York. She said she had never been a member of the Communist Party. She had, though, in her youth: if she had been looking for a boyfriend, she soon found out she was looking in the wrong place.

Her left wing views stayed with her, and when they came in to conflict with her pacifist instincts following Tony Blair’s role in the 2003 invasion of Iraq, she could not bring herself to vote other than Labour.

Although I lean gently left, I’m not comfortable with the tribal approach. I was furious at what I saw as Blair’s betrayal over Iraq: George W. Bush clearly wanted his war with Iraq as “revenge” for the 9/11 attacks, although Iraq had nothing to do with them. This came not so much from a pacifist viewpoint as a pragmatic one. There was no reason for Britain to support Bush: why were we sticking our head in this hornets’ nest – don’t we always end up making it worse? Were we going to try to overthrow every unpleasant regime in the world? So I rejected Labour and voted for the Liberal Democrats in the 2005 election.

In 2019 I couldn’t stomach Jeremy Corbyn’s politics, and campaigned for our former Conservative MP David Gauke, who was forced to stand as an independent when his party deselected him for battling tirelessly in parliament to avoid a disastrous no-deal Brexit. My mother must have been turning in her grave that I could vote for even an ex-Tory.

In the 2019 election there was a huge divide between the two main candidates, with Corbyn on the far left, and Johnson’s only ideology being Boris, albeit positioned for right wing support. This gave the Lib Dems plenty to aim at in the middle ground. But the Tories’ “Get Brexit Done” message proved popular, and many were put off voting Lib Dem for fear of letting in Corbyn.

In 2024, the Lib Dems faced a different landscape. In theory they were well placed to benefit from protest against the brutally exposed false promises of Brexit, and the years of often chaotic Conservative government. In practice, nobody wanted to talk about Brexit, judging the public sick and tired of it. And with Keir Starmer’s Labour occupying the centre ground, there was little political space left for the Lib Dems, only differences of emphasis.

So their plan was to position themselves to receive the anti-Conservative vote, and the campaign became tactical more than ideological: the mission was to persuade voters that they were best placed to defeat the Tories. Within days of Sunak’s announcement I was back on the streets enthusiastically delivering my first batch of leaflets. Before the first leaflet went through the door a questionable assertion leapt out at me:

A large graphic claimed that “It’s clear that only Lib Dem Sally can beat the Conservatives here.” Unfortunately the Lib Dems have form for selective or dishonest presentation of statistics, so back home I measured the bars on the chart. On the figures given, the Labour bar should have been about 30% of the height of the Lib Dems bar: it was actually barely over 20%. The Lib Dems were up to the same old tricks again.

More importantly, it used local election results to justify this claim: this is highly suspect, as local and national elections produce very different results. The first port of call to fact-check the claim was the tactical.vote website:

In fairness, there were complications in our constituency. In 2019, David Gauke stood as an independent and achieved a 26% share of the vote, so we could only guess how those people would vote this time. Perhaps the 2017 election would have been a better guide. In addition, substantial boundary changes make like-for-like comparisons difficult – the new constituency contains only 57.1% of the old constituency’s population. So although the tactical voting website seemed carefully researched it could have been mistaken. But of course to the extent that the website wields some influence and nudges the anti-Conservative vote towards the same party, it might be partly self-fulfilling.

Sometimes bookmakers’ odds are a more reliable predictor of results than opinion polls: the bookies have to back up their prices with hard cash. You can find “Politics” on their websites listed without apparent irony as a sport, typically nestling between Netball and Rugby League. So I found that bet365 make prices on every constituency: ours looked like this:

Wow! Labour odds on to win, in what had been regarded as a rock-solid Conservative seat. And Labour’s 8/13 price – compared to the Lib Dems 66/1 – suggests that bet365 had a hugely different view about who was most likely to threaten the Conservatives from the one expressed on our leaflets. The claim that Labour were in a “distant third place” looked extremely doubtful.

The verdict of the tactical.vote website combined with the generous potential returns offered to those willing to back the Lib Dems made me very sceptical of our claim to be best placed to beat the Conservatives. It seemed that the moment I started delivering these leaflets I was complicit in a brazen lie.

So what, you may say, politicians lie, and they always have done. True, of course: all parties have been caught at it during the election. The trouble is, it works, and voters seem happy to vote for proven liars: Donald Trump and Boris Johnson have lied habitually and been well rewarded for it. The Leave campaign in the Brexit referendum was built on false promises and deceit, notoriously the bus stating “We send the EU £350 million a week – let’s fund our NHS instead”. Completely misleading tripe? Of course, but the figure was out there, and some people believed it.

But the Liberal Democrats…weren’t we supposed to be the good guys? No doubt I was being naïve: if everyone else fights dirty, we’ll get thrashed if we’re still following the Queensberry Rules. Thus the stench of politics can infect its humblest foot soldiers.

Notwithstanding my reservations, I attended a pleasant drinks party on a sunny Sunday afternoon in a beautiful garden in Rickmansworth. Our candidate Sally Symington gave supporters a pep talk, hammering home the message that we would never have a better chance to get rid of the Tories, and that she was the only candidate who could defeat them. The reasons she gave were compelling: the incumbent Conservative MP Gagan Mohindra was not popular, having been rarely seen in the constituency apart from the occasional photo shoot, and was widely regarded as missing in inaction: meanwhile Labour had declared SW Herts as a non-battleground constituency – to the extent that allegedly if their candidate even campaigned in the constituency she would not be selected again for the party. Among the supporters there was widespread agreement that if David Gauke was still the Conservative candidate, it would have remained a much safer seat for the Tories.

Thus encouraged, I became a tireless workhorse for the Lib Dems, delivering many batches of leaflets to multiple roads. There was a nostalgic pleasure in delivering to the road where I lived as a child in Chorleywood, where I had done two separate paper rounds over fifty years ago. It hasn’t changed much. I remembered a large house that used to be called Wild Folly: my parents were most amused during the 1966 election when they put up a large Vote Conservative poster. Unsurprisingly the house now goes by a different name.

Given that my preference for the Liberal Democrats over Labour was marginal at best, it troubled me that leaflet by leaflet I might be helping the Tories by moving votes away from their strongest opponents. Nationally that would hardly matter: Hertfordshire South West was the 105th safest Conservative seat according to electoralcalculus.co.uk. If the Conservatives came anywhere close to losing our seat then Labour would have a huge majority in parliament.

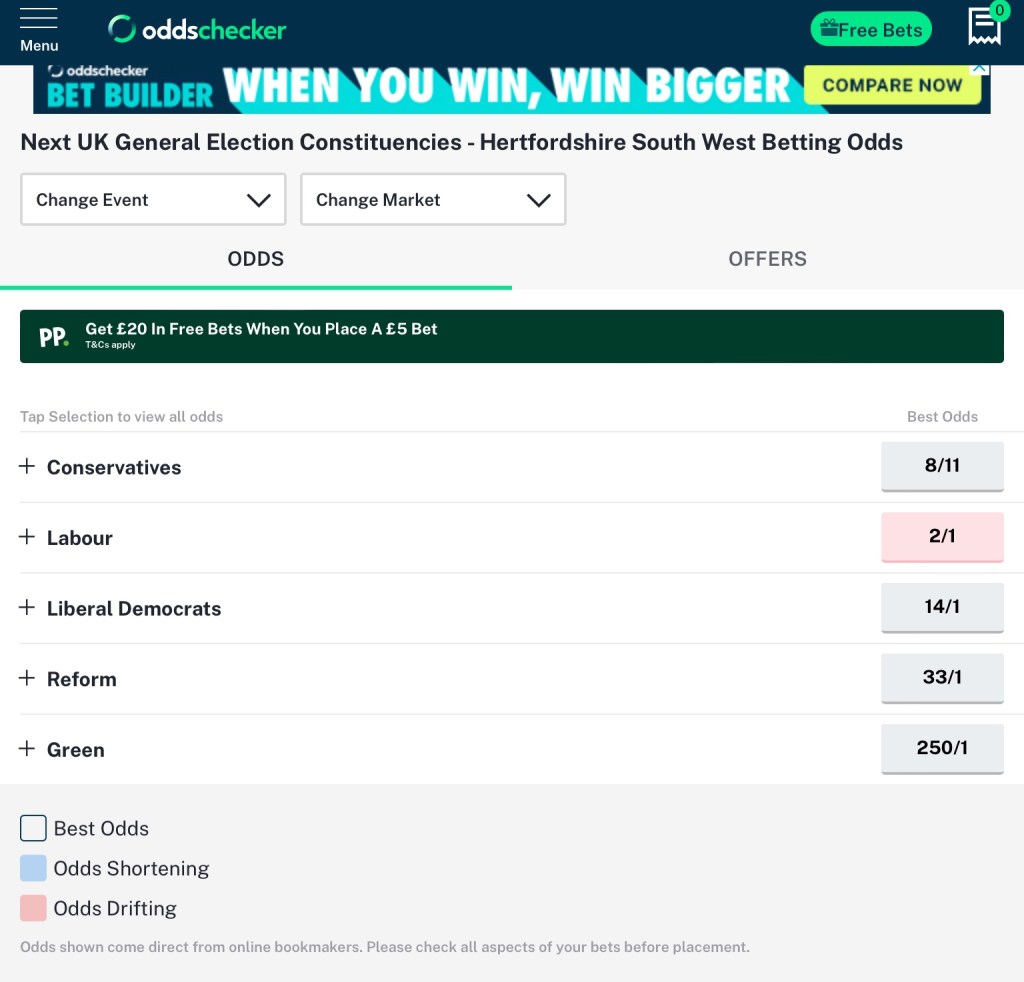

Over the course of the campaign, Labour’s odds in the constituency drifted from 8/13 to 2/1 despite their odds on the national vote shortening.

This could have been due to their almost invisible campaign (their candidate was from Camden in north London – were they even trying?). Or perhaps their initial odds had only been so short because of some heavy betting by politicians? Meanwhile the Lib Dems’ odds had come rattling in from 66/1 to 14/1, at one point getting down to 8/1. I like to think that the energetic Lib Dem campaign shifted the dial. We certainly out-delivered the opposition by so much we could be accused of spamming: at our house this was the tally of election leaflets received:

- Conservatives: 4

- Green: 1

- Labour: 1(!)

- Liberal Democrats: 9 (of which two were personally addressed)

- Party of Women: 1

- Reform: 1

- Rejoin: 1

That’s right. There were as many leaflets for the Lib Dems as there were for the rest put together.

Late in the campaign the tactical.vote website was getting excited about the opportunity to “destroy the Tory party for good”:

This was reckless wishful thinking. The Conservative Party wasn’t about to disappear, no matter how poor its results. And tactical.vote should be careful what they wished for: what would emerge in place of the Conservatives to represent the British right? Would Farage the Unflushable get his wish for Reform to take their place?

At last polling day dawned, and speculation would soon be replaced by results. I did a stint of telling at our local polling station sporting a rosette and found it quite pleasant. The sun shone, although when it went behind a cloud it felt unseasonably chilly – but still much better than the freezing rain in December 2019. Voters were mostly happy to show me their polling cards, and several volunteered that they had voted for the Lib Dems.

There were no tellers from other parties. Labour’s absence was unsurprising, given their invisibility during the campaign, but I was taken aback to see no Conservative teller. I took this as a sign of low morale in the party, and a lack of enthusiasm for their candidate.

One man took the opportunity to have a go, declaring that the Lib Dems were a “shower” who were campaigning on only three of the fifteen issues which mattered most. I pointed out that as a teller I wasn’t allowed to discuss it with him, but he continued until I reminded him that I could only be a punchbag in this conversation and eventually he left me alone.

But the nice fellow who worked at the hall brought me out a cup of coffee, a few familiar and friendly faces came in to vote, I got to mind a couple of dogs – trying to calm their anxiety while their mums disappeared into the building – and most voters were pleasant, or at least civil. I felt privileged to be a tiny part of the election machinery, witnessing democracy in all its majesty.

At 10 pm we tuned in for the exit poll, which predicted a Labour landslide, in line with opinion polls throughout the election period. It came impressively close to predicting the final state of the three biggest parties – out by just two in the case of Labour:

| Party | Exit poll forecast seats | Final seats | % of seats | % of popular vote | Implied seats under PR |

| Labour | 410 | 412 | 63.4 | 33.7 | 219 |

| Conserv- ative | 131 | 121 | 18.6 | 23.7 | 154 |

| Liberal Democrats | 61 | 72 | 11.1 | 12.2 | 79 |

| Reform | 13 | 5 | 0.8 | 14.3 | 93 |

| SNP | 10 | 9 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 16 |

| Plaid Cymru | 4 | 4 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 5 |

| Green | 2 | 4 | 0.6 | 6.4 | 42 |

| Others | 19 | 23 | 3.5 | 6.5 | 42 |

| Total | 650 | 650 | 100 | 100 | 650 |

But as Professor John Curtice stated, he was much less confident of his predictions of the number of seats the smaller parties would win: in the event Reform got fewer seats and the Greens more than predicted. There was also much more confidence in the overall figures than there was in the predictions for individual seats.

And astonishingly the exit poll showed South West Herts as a Labour gain when applied to the BBC swingometer.

Later in the night, the actual result was announced:

Mostly I was disappointed that the Conservatives had held the seat. If they didn’t lose it this time, they probably never will. But I was also relieved that the Lib Dems had, at least, justified their claim to be best placed to beat them, coming a comfortable second. I had not, it turned out, been spreading lies on their behalf.

How could the tactical.vote website – and the bookies – get it so wrong? The tactical voters were all being sent in the wrong direction. The aggregate Lib Dem plus Labour vote exceeded the Conservative vote by over 5,000 – if half the people who voted Labour had switched to the Lib Dems, the Conservatives would have lost. That said, Reform plus Conservative exceeded Labour plus Lib Dem by 1,609 votes, so the Conservatives didn’t really come close to losing the seat.

Perhaps tactical.vote failed to take account of the Labour Party’s almost complete absence from the local campaign. Why would constituents give them their vote, when they were all but invisible? – especially compared to the Lib Dems’ energetic campaign. Perhaps a quiet, behind the scenes deal between those two parties carved up the seats, and South West Herts was given to the Lib Dems – or perhaps more likely a set of informal local understandings. In any event, the Lib Dems’ strategy succeeded nationally beyond all their best expectations, winning them 72 seats – their best result since Herbert Asquith was their leader.

Nationally, of course, the fate of my constituency is irrelevant – Labour have a huge parliamentary majority. Strikingly, they won 63.4% of the seats from just 33.7% of the popular vote – the lowest vote share of any majority government in British history. Peter Mandelson explained that the Labour Party’s strategy had been to single-mindedly (and very successfully) target winnable seats rather than aggregate votes. With the turnout being just 59.75%, some people have pointed out that they have formed a government with support from just 20.1% of the electorate. But this statistic should not be given any weight. If people can’t be moved to vote, they should not expect their voices to be heard – except perhaps as a measure of apathy and disillusionment.

Nevertheless it is impossible to ignore the huge mismatch between vote share and the outcome in terms of MPs. Ironically the Liberal Democrats, long time supporters of electoral reform, successfully worked the system to get a fair(ish) number of seats for their votes, gaining only seven fewer MPs than a strictly proportional allocation would have given them.

| Party | Votes | Seats | Votes per seat |

| Labour | 9,731,363 | 412 | 23,620 |

| Conservative | 6,827,112 | 121 | 56,422 |

| Liberal Democrats | 3,519,163 | 72 | 48,877 |

| SNP | 724,758 | 9 | 80,529 |

| Reform | 4,106,661 | 5 | 821,332 |

| Green | 1,943,258 | 4 | 485,815 |

The biggest losers from the first past the post system were Reform, who totalled over 820,000 votes for each seat won – nearly 35 times as many votes per seat as Labour. Next were the Greens, who averaged about 485,000 votes per seat. It will be interesting to see whether these very different parties make common cause to campaign against the unfairness of the electoral system. Also, perhaps to hear ex-Conservative, now Reform politicians suddenly turn against the first past the post system which they have supported for so long.

In 2011 the electorate decisively rejected changing to the Alternative Vote system by 68% to 32%. The Conservative and Labour parties have consistently defended the existing system – they would, wouldn’t they? – as one that can usually deliver strong governments. That’s one thing they always seem to agree on. And looking at the current situation in France, they may have a point. But in 2024 the aggregate vote of these two parties was just 57.4%, their lowest share since 1918. If their combined support continues to erode, pressure to change the voting system can only grow.

What if we already had an electoral system that allocated seats in proportion to votes? Of course people might have voted differently under another system, but as it stood 2024 election would have given us 219 Labour, 154 Conservative, 93 Reform, 79 Liberal Democrat, 42 Green and 16 SNP MPs. What would have happened? Even together, Labour and the Liberal Democrats could only have mustered 298 seats, so the most likely result would have been a broad coalition encompassing the Greens, and possibly also the SNP and Plaid Cymru to get comfortably over the 325 threshold for a majority. Suddenly our parliament would look very European. Reform UK would have loved that.

***************

If I thought I was done with delivering election leaflets for a while, I was mistaken. Another batch soon arrived on my doorstep, thanking voters for their support. Why were we taking a victory lap after finishing second? No-one had heard a peep from Gagan.

It was mainly to remind Labour and Green voters that we could have beaten the Tories here if they had voted for us instead. True, but selective: the chart omits Reform UK, with its 14% vote share. If the Lib Dems can add in Labour and Green, the Tories have to be allowed to add in Reform. If nothing else, the Liberal Democrats should be in position to receive the tactical vote recommendation at the next general election. Assuming, that is, there is still an appetite for an anti-Tory alliance by then. That will depend on the performance of the new Labour government.

The leaflet also sought to recruit volunteers for leaflet delivery. I hope we get some. I could do with another person to share the load.

Leave a reply to Rik Cancel reply