The Yorkshire Dales are very beautiful, but they have many wet days, and when I was about twelve, it was on one such day when I found a volume of Believe it or Not! by Ripley in a secondhand bookshop in Dent, which I bought for 2/6d. I had never seen the newspaper series, and the parade of bizarre “facts” and lurid illustrations gripped me in morbid fascination.

I wasn’t the only one. At school our English master, an unenthusiastic man – who had long ago been nicknamed Beery – no doubt keen to get his marking done in school time, encouraged us to set up a class library. We each had to bring in a couple of books to make up the stock. If he thought we’d be discovering Dickens, Twain and Orwell he was disappointed. There was virtually a stampede to get hold of Believe it or Not!.

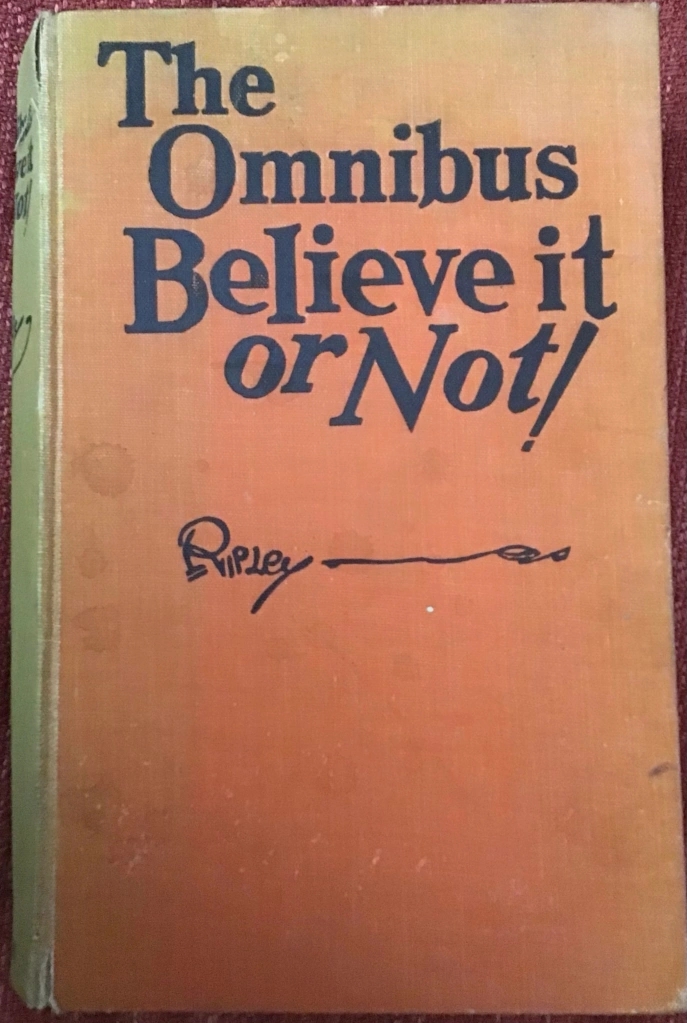

That book got chucked out once I was old enough to see it for the sensational, freak show nonsense it was. But a few decades later, curiosity got the better of me again, and I picked up online a slightly different edition – an “Omnibus”. I was joyfully reunited with Yogi Haridas, the famous Ascetic who could touch his forehead with his tongue, and Simon of the Pillar, the Syrian who sat on top of a marble column in Alexandria for 69 years without descending once. Much of the content appears racist to modern sensibilities, but can also be seen as an innocent and entertaining – if perhaps unreliable – look at the bizarre and the unlikely.

Ripley made much of his travels to distant and exotic lands, but most of the items he used came from his researcher Norbert Pearlroth’s tireless research in the New York Public Library. Ripley claimed to be able to “prove every statement he made” but more realistically, perhaps, he meant that he could refer it back to a source in the library. It seems unlikely that Ripley would have allowed the facts to get in the way of a good story – in fact, he liked to be called a liar. In his preface he writes:

I venture to say that I have been called a liar more often than anybody in the world. Ordinarily when one is called a liar – well, to say the least, one feels hurt. But it is different with me; I feel flattered. That short and ugly word is like music to my ears. I am complimented, because it means that my paragraph that day contained some strange fact that was unbelievable – and therefore most interesting, and that the reader did not know the truth when he saw it. That is the time when I always think of the comment made by Hamlet on a certain occasion:

"There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy."

Ripley's is still a thriving franchise with visitor attractions around the world. But is much easier to check facts in the internet age than it was when Believe it or Not! was in its heyday in the 1920s, 30s and 40s - or indeed, when I was gorging on these oddities in the late 1960s.

So, reunited with this strange and sensational book, I have the opportunity to satisfy the curiosity of my twelve year old self, armed with Google, Wikipedia and the rest of the internet. Not to mention Guinness World Records, who apply a much more rigorous approach to verification than Ripley ever did.

So here goes. Let’s start with an easy one.

***************

100 yards is 91.44 metres. The current record for 100 metres is 9.58 seconds, set by Usain Bolt in 2009, so this equates to a 100 yard time of 8.76 seconds. So Mr See could hop the distance just 2.24 seconds slower than Bolt could run it? Hmm. Let’s see what Guinness World Records has to say.

The fastest 100m hopping on one leg was set by Rommell Griffith (Barbados) in 15.57 sec as part of the Barbados World Record Festival at the Barbados National Stadium, St Michael, Barbados on 31 March 2007.

So Rommell would have passed the 100 yard mark in about 14.2 seconds. Do we think that S.D. See could have been 3.2 seconds inside the modern verified record?

VERDICT: Not!

***************

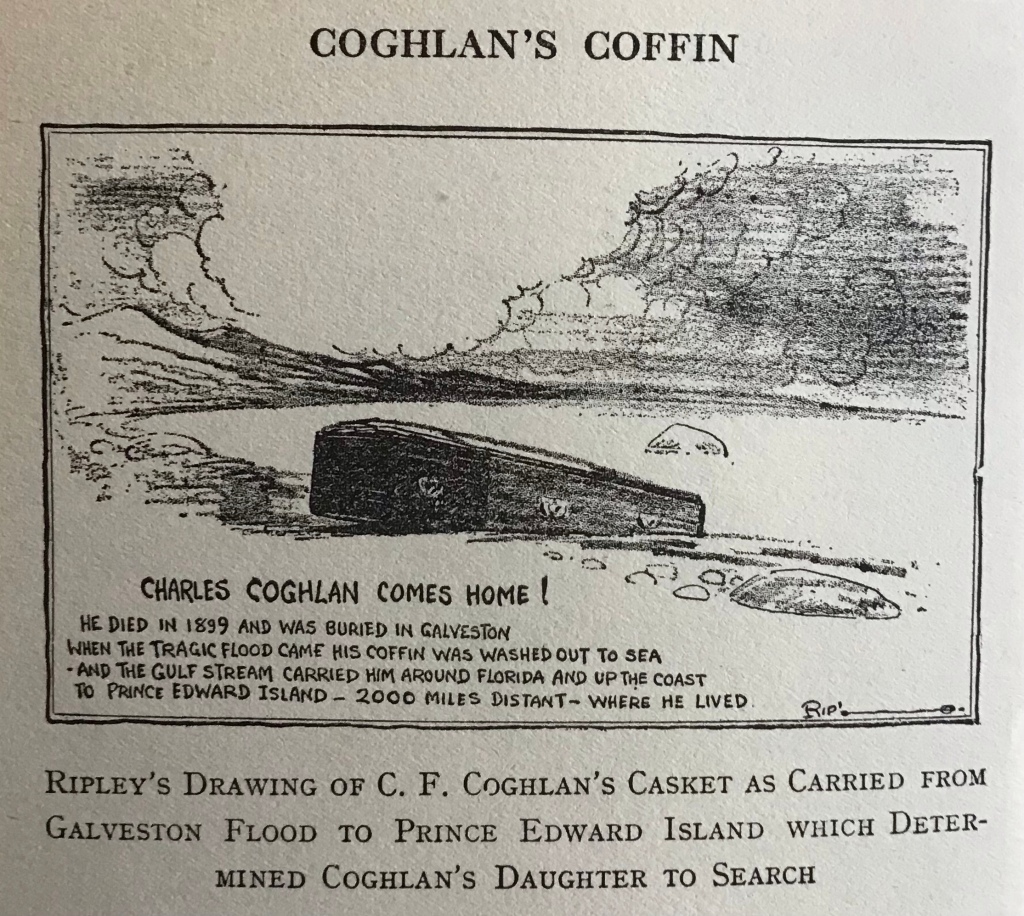

According to Wikipedia, actor and playwright Coghlan’s casket was swept away from its resting place by a storm surge generated from the deadly Galveston Hurricane of 1900. The coffin and remains were found in January 1907 by hunters, in a marsh some nine miles from Galveston. The story that Coghlan’s casket had been recovered near his home on Prince Edward Island arose much later, first appearing in print in 1925, leading one wag to dub it the “homing coffin”. Ripley repeated this story in his Believe it or Not! column in 1929.

So who are we going to believe…Ripley or a fully sourced Wikipedia entry?

VERDICT: Not!

***************

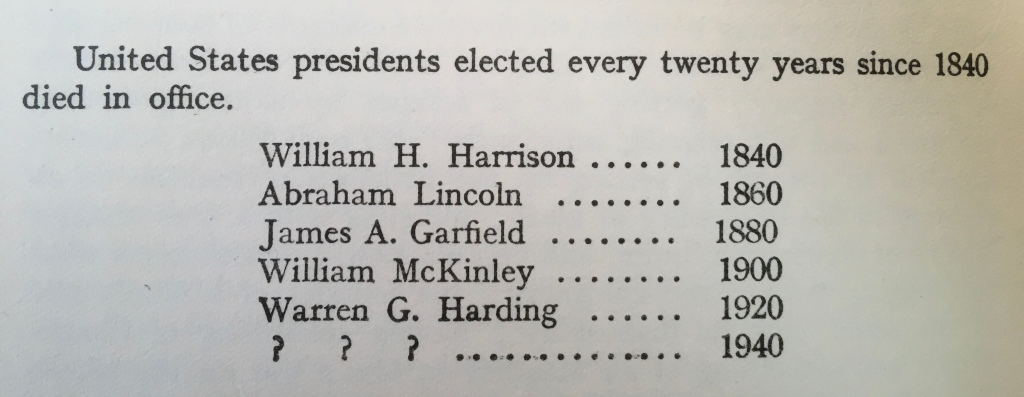

- William H. Harrison was the first U.S. president to die in office, on April 4, 1841, just one month after Inauguration Day. He died from complications of what at the time was believed to be pneumonia.

- Abraham Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth on the night of April 14, 1865, and died the following morning. He had just begun his second term of office, having been elected on November 6th 1860.

- James A. Garfield was shot by Charles J. Guiteau, surviving for over two months before dying on September 19, 1881.

- William McKinley died eight days after being shot by Leon Czolgosz on September 6, 1901.

- Warren G. Harding suffered a heart attack, and died on August 2, 1923.

- Those ominous question marks against 1940 proved prescient. Franklin D. Roosevelt had won elections in 1932, 1936 and then won unprecedented third and fourth terms in 1940 and 1944. On April 12, 1945, soon after beginning his fourth term in office, he collapsed and died of a cerebral hemorrhage.

- And of course, John F. Kennedy, elected in 1960, was assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald on November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas.

So the grisly sequence described by Ripley of five presidents dying in office over a period of 80 years eventually extended to seven presidents and 120 years. The sequence was ended by Ronald Reagan, who was elected in 1980. He survived an assassination attempt in 1981, just 69 days after taking office, and went on to complete two full terms.

This pattern of incumbent deaths came to be known as the Curse of Tippecanoe, or the Curse of Tecumseh, the name of the Shawnee leader against whom William H. Harrison had fought in the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe.

VERDICT: Believe it!

***************

Hmm, well…the beaked chaetodon, also known as the copperband butterflyfish (Chelmon rostratus) is indeed a fish. And there are fish which shoot down prey above the water, but they are the more appropriately named archerfish. I can’t find any evidence that the beaked chaetodon hunts this way. So, close, but…

VERDICT: Not!

***************

It’s a nice idea, but the only references I can find to such an event refer back to Believe It Or Not! It’s also unclear who Hué was – perhaps Ripley meant Charles Désiré Hue, the French artist? I wonder what he was supposedly arrested for? I’m pretty sure the story is apocryphal, but you never know…

Verdict: Believe It Or Not!

***************

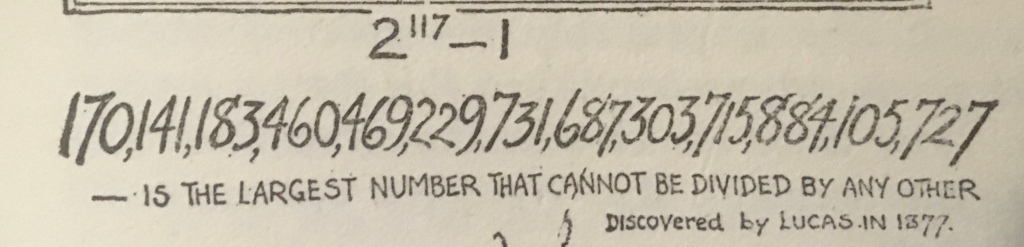

Firstly, the number he gives is not 2117− 1, which is actually a mere 166,153,499,473,114,484,112,975,882,535,043,071, less than one thousandth of the number he gives. His number is actually quite close to 2 to the 127th power, sharing the first 16 digits, but then it diverges. It’s possible to test whether Ripley’s number is indeed a prime by dividing it by each prime up to its square root, but I haven’t done that. Sheer laziness. But I haven’t found his number on any list of primes.

There is, however, a set of numbers called Mersenne primes, which are one less than a power of two. At the time of writing, the six largest known primes are of this type, because it is easier to test them for primality. But if Ripley’s number is prime, is it still the largest known prime number? No, because as of January 2024 the largest is 282,589,933 − 1, a number which has 24,862,048 digits when written out in full, like this:

148894445742041325547806458472397916603026273992795324185271289425213239361064475310309971132180337174752834401423587…you get the drift. I haven’t tested this one either, although I have a sneaking suspicion it divides exactly by 7.

If Ripley’s number is prime – which I doubt, as it isn’t on any list of prime numbers I’ve found – it may have been the highest known at his time of writing. But it is not 2117− 1 as he claims. Also he has phrased his statement wrongly. Because his number can be divided, for example, by 2 (leaving a remainder of 1) and by 5 (leaving a remainder of 2). He neglected to say without leaving a remainder. Sloppy all round.

VERDICT: Not!

***************

This story seems to be confirmed by the Wikipedia page on Captain Hedley, and British born Hedley emigrated to the USA in 1920, becoming a regular on the lecture circuit, thrilling audiences with tales of his wartime adventures.

We only have the word of Captain Hedley and Lieut. Makepeace that this extraordinary event happened, but Ripley was certainly quoting an established story. Meanwhile the military records confirm that he was credited with eleven aerial victories, and that he survived being shot down in March 1918, and spent most of the rest of the year as a prisoner of war, and that he received the French Croix de Guerre. Given that track record one might be tempted to give him the benefit of the doubt: however, Legion, the Canadian military history magazine, writes that a newspaper story reported Hedley’s speech to a Rotary Club luncheon in the United States thus:

“Captain Hedley described an experience which he had as an observer. Observers were not strapped in the airplanes and when the pilot caused the machine to dive suddenly, Hedley was thrown forward in the air. He had, however, retained his grasp on the machine gun and when the ‘plane straightened out he was flung back upon the fuselage. He then managed to crawl back into the cockpit.”

If so, his was still a terrifying ordeal and an amazing and courageous escape, but not quite the stroke of extreme luck described by Ripley. Sadly, Lieut. Jimmy Makepeace – probably the only other person who knew what happened on that day, did not survive the war. He died in May 1918 when his fighter plane suffered structural failure in flight.

VERDICT: Believe It Or Not!

***************

Hmm, I don’t think so. According to a scholarly article on the Butterfly Hobbyist website, there are many theories as to how butterflies got their English name.

- The word may come from the Old Dutch word boterschijte, which translates to “butter crap.” Butterfly excrement is bright yellow when they first emerge from their chrysalis.

- Some think the Dutch term boterschijte arose because butterflies commonly eat animal faeces.

- Old German names for the English word butterfly include “botterlicker,” “milchdieb,” and “molkendieb.” “Botterlicker” translates to “butter licker.” “Milchdieb” translates to “milk thief.” Some think that those who churned butter and created dairy products often spotted butterflies sucking on the leftover liquids and gave the butterflies their Old German terms.

- The Anglo-Saxons used the word “buterfleoge” to refer to butterflies. Buterfleoge means “butter” and “flying creature.” Some suggest they called it this because the butterfly they most commonly saw was the yellow brimstone. However, this theory is doubtful since there are thousands of species of butterflies, most of which do not have yellow wings.

- The word butterfly could have also been derived from the Old English word “bēatan,” which means “beat,”, as in beating wings, and the Old English word “Flēoġe,” which means “fly.” The word buterfleoge eventually evolved into the Middle English term “butterflie.” There is evidence of 15 different spellings of the word before the Modern English spelling of butterfly.

- It is said Anglo-Saxons believed witches would turn into butterflies at night and steal butter. This belief could have led to people referring to butterflies as “butter creatures.” A similar spelling of the Old English term for butterfly is buttorflēoge, which means “an insect that flies at night.”

All of which suggests that we don’t really know the etymology of this branch of entomology. but the notion that the butterfly was originally called flutterby does not stand up to the briefest inspection. Flutterbys don’t make any appearance in writing before 19th century nonsense literature. Butterflies certainly Flutter By, but they have only been called that in jest. Or perhaps by the Reverend Spooner.

VERDICT: Not!

***************

Luckily the fact checking website Snopes has already had a look at this one. The story is also told about Napoleon Bonaparte saying this in 1799, resulting in the unintended massacre of 1,200 Turkish prisoners. So the first question is – which is it? Probably neither. Snopes lists the problems with this story:

- this account doesn’t match any real event in recorded history. There was indeed an incident involving the slaughter of over a thousand prisoners captured by Napoleon’s troops during the French invasion of Syria in 1799, but it was a deliberate act ordered by Napoleon.

- nor does the story stand up linguistically. The English equivalent of “massacrez tous” would be “massacre them all” – quite a formal phrase to come out with under pressure. Just as an English speaker would be more likely to say “kill them all!”, so a French speaker would say “tuez-les tous!”

- Napoleon Bonaparte’s nephew, Louis-Napoleon (Napoleon III) did indeed lead a successful coup d’état on 2 December 1851. Louis-Napoleon bore the title of President and sought to dissolve the National Assembly and establish himself as Emperor. A few hundred protesters who had set up barricades in the streets of Paris were killed as Louis-Napoleon consolidated his coup: this was no accident, but a deliberate military action.

It seems likely that, like OPQRST above, this is a schoolboy joke which Ripley has shoe-horned into history. Snopes was unable to find any reference to this story before it appeared in Believe it or Not!

VERDICT: Not!

***************

Conclusion

I have looked at nine Believe it or Not! assertions, finding three unproven and five untrue. The one that is definitely correct – about the US presidents who died in office – would have been very easily disproved at the time it was first published had it not been true, so it had to be. The others would have been more difficult to verify or disprove, giving Ripley the opportunity to publish a wide range of unproven and sensational stories.

Ripley often claimed that everything appearing in his newspaper features had been verified as true, and wrote that being called a liar was “music to his ears” – taking it as evidence that he had unearthed an interesting and barely believable fact. I don’t believe he invented his ‘facts’ but he was hardly rigorous in his verification – if any other source had asserted them, that seemed sufficient proof for him.

But Ripley’s flair for self-promotion and publicity gave his newspaper features a very high profile: generations of readers grew up believing what they read there, and a large number of apocryphal ‘facts’ became established in the popular memory. It seems that sensational and poorly sourced assertions predate clickbait, and that fake news was around before the internet. A few millennia before, I’m guessing.

Leave a comment