In December 2009 I sat in the Birmingham office of an accountancy firm, turning in my hands a gemstone which had been valued at eleven million pounds. I had the chance to buy it. How much should I bid?

*********************************

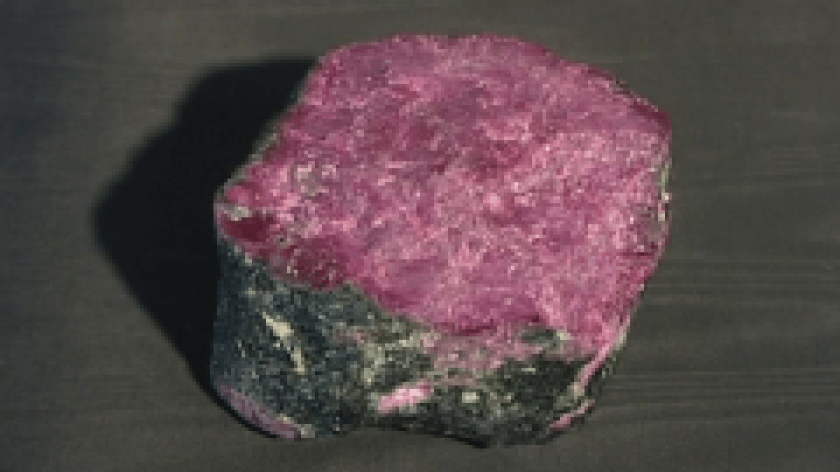

On 10th March 2009, Wrekin Construction, a private civil engineering business based in Shropshire with about 500 staff, collapsed into administration, owing creditors over £20m. Its main asset was a 2.1 kilogram lump of crystal, grandly described as the Gem of Tanzania in the company’s accounts, where it was valued at a princely £11m.

The stone had been discovered by Ideal Standards, a company mining near Arusha, a small town in northern Tanzania. Michael Hart-Jones, an investor in Ideal, bought the gem in 2002 for R200,000, or about £13,000.

Hart-Jones was a colourful character. He had been convicted of illegal diamond trading (wrongly, he said) in South Africa in the early 1980s. Then, according to official testimony from Ahmad Kabbah, the elected president of Sierra Leone restored to power in 1998, Hart-Jones had struck a deal with the illegal junta there the previous year to exploit its mineral resources, in return for facilitating a $1bn loan for the junta. Finally, a BBC2 Newsnight report from 2006 featuring Richard E Grant suggested that Hart-Jones had promoted a scam in Swaziland (now Eswatini) selling goat serum as an Aids treatment.

Mr Hart-Jones exported the ruby to the UK in 2002, but initially struggled to find a buyer. The next recorded owner was Tony Howarth, director of a foreign exchange company. Howarth sold the stone to Shropshire based businessman David Unwin in 2006, through a deal also involving land and Rolls-Royce cars, which valued the gem at £300,000. The gem was recorded at the same value on the balance sheet of Unwin’s company Tamar Group that year.

Tamar Holdings took over Wrekin Construction, and the gem received an astonishing revaluation to £11m in 2007:

Wrekin had acquired, at a cost of £11m in shares, what it described as “a ruby gem stone known as the “Gem of Tanzania”’ from its shareholder, Tamar Group Limited. The notes to the accounts went on to say that the fair value of the gemstone was determined by a professional valuer at the Istituto Gemmologico Italiano.

As it was purchased using shares rather than cash, the inclusion of the gemstone in the balance sheet at £11m helped raise Wrekin’s net assets from a negative £7.6m to a positive £6.3m. This made the company appear a more creditworthy partner for suppliers, customers and its bank, Royal Bank of Scotland.

Wrekin’s auditors for the nine month period ended 31 December 2007 were Ashgate Corporate Services Limited, a small Derby firm who had recently succeeded “big four” firm KPMG as auditors – a change which might itself have been read as a warning sign. Ashgate might have been surprised to see that a civil engineering business based in Shropshire, with turnover for the period of £60.9m and profit of £1.6m (against a loss of £9.5m the previous year) had decided to make a huge investment so far outside its core business.

A more alert auditor might have asked a few questions: most obviously, why would a construction company invest £11m in a gemstone? Was this a genuine arms-length transaction with its shareholder? Why had they chosen to get it valued in Italy? And why had nobody heard of this amazing gemstone, when the highest previous verifiable price for a ruby – the 8.62 carat Graff ruby sold by Christie’s in 2006 – was a mere $3.6m?

Ashgate were presented with a letter, purporting to be from the Istituto Gemmologico Italiano, confirming the valuation, and containing a photograph of the gemstone. That was good enough for them, and they duly signed off the accounts.

It is not known whether RBS’s decision to grant a £4.25m overdraft facility was influenced by the borrower’s ownership of the gem. According to a former Wrekin representative, RBS had lent the company £2.8m of that at the time of administration: perhaps they saved themselves the last £1.45m by finally taking a good look at Wrekin’s accounts.

Nor is it known what triggered the collapse of Wrekin Construction into administration, but it may be that bank lenders pulled the plug when they finally inspected the company’s balance sheet and saw what was propping it up. Initially Wrekin blamed RBS for its predicament because the bank would not extend credit to cover cash-flow problems.

Jonathan Guthrie of the Financial Times pieced together the story, and interesting and bizarre details emerged over the months of 2009.

Loridana Prosperi, a gemmologist at the head office of the Istituto Gemmologico Italiano in Milan, said of the valuation letter: “That is impossible, because we were on holiday on August 31 2007.” She said IGI never assessed the price of gemstones, only the quality – and the Valenza office did not even do that. It was soon confirmed that the valuation letter had been forged, but it was not established by whom.

Ernst and Young had been appointed as administrators, and they appointed GVA Grimley as their agents to dispose of Wrekin’s assets, of which the highest profile – if not the most valuable – was the gem. Ernst & Young consulted with experienced gemmologists, and determined that the ruby was opaque and of insufficient quality for faceting, meaning that it could be cut into smaller rounded, gems – or cabochons – but not into jewels with flat facets with an attractive sparkle.

They concluded however that if was of “sufficient quality and rarity” in its uncut state “to be of interest to public and private collections”. “It is not possible” they continued, “to place a value on the uncut stone, given its unique nature and consequent absence of comparable data. Any attempt to provide a potential range of valuations may prejudice future realisations”. In other words, because of its notoriety, the stone now had the potential to far exceed its value as a regular gem at auction.

It seems that top London auction houses rejected the gem because they deemed its value too low. Ernst & Young were reduced to advertising the sale in Rock ‘n’ Gem – a quarterly UK magazine, read by mineral collectors and devotees of “healing” crystals. The fact that Ernst & Young sought to sell the stone as a specimen was taken to imply that they were doubtful whether it could be cut profitably into individual jewels.

Hatton Garden gem dealer Marcus McCallum’s view was sought: “The Gem of Tanzania may not be worth the cost of the advert. A two kilo lump of anyolite (low grade ruby) is probably worth about £100. A valuation of £11m would be utterly bonkers.” Wrekin owner David Unwin was said by his lawyer to be “devastated” by the damage to his reputation caused by doubts over the value of the gem.

On behalf of Ernst and Young, GVA Grimley duly initiated an auction of the gem. The Financial Times saw it like this:

We should not, however, remember the gem as having failed to cut it as a polished crown jewel. It should instead be remembered as a staggeringly successful healing crystal. Though its mystical powers failed to prevent Wrekin Construction from folding, its mere presence on the company books clearly made group finances look and feel much healthier.

Like most new-age medicine, the stone derived its power from the faith of those who believe – in this case in its intrinsic ability to rise perpetually in value. The Gem of Tanzania was a magnificent placebo asset. In these straitened times, there must be many who would benefit from the gem’s awesome power. At the very least, the stone would make an excellent – if rather unattractive and unwieldy – paperweight. So, who will start the bidding?

I recognised a call to arms: here comes my cameo in this drama. 2009 had been an excellent year, and I had some cash to “invest”. The opportunity to acquire something recently so spectacularly valued was too good to ignore. The quality of the stone as a gem may have been questionable, but it was famous as the basis for a world-beating piece of bullshit. And my wife had a big birthday coming up. That could make a wonderful surprise gift. Er, couldn’t it?

I had very little idea where to pitch my bid: I can only repeat in my defence that, fuelled by the prospect of an excessive City bonus, I was feeling flush. I indicated what I regarded as a substantial bid to GVA Grimley. Within a few days they contacted me to advise me that I was among the top ten bidders, and offered me an appointment to view the gem.

So on a snowy 21st December I bunked off the morning at work (it wasn’t very busy) to attend Ernst and Young’s Birmingham office at 9:30 am to view the gemstone. Two men in suits ushered me into the presence of the stone. which I was allowed to handle. I solemnly turned it over for inspection. Of course I’m no gem expert, so I was none the wiser – it was a large, rough, reddish lump of rock, by no means beautiful.

They asked me if I wanted to increase my bid, and I did, slightly, to £5,679.00. As requested I left it with them for six weeks, while they continued to solicit bids and while the creditors’ committee decided on its course of action.

The 2nd February deadline passed and I had heard nothing. Growing impatient after a while, I contacted Jonathan Guthrie – journalists at the FT were still surprisingly accessible at the time, even supplying their email addresses under some articles – telling him that I had put in a bid and heard nothing back. I speculated that the administrators might have received better bids – or perhaps they were dithering about whether to accept the best bid. I was hoping that the FT would be able to flush out what had happened. Mr Guthrie did not disappoint: this appeared after a few days:

No prizes for identifying the “bidder anxious to know the outcome of the auction”. I thanked Mr Guthrie with the message “Anonymity at last!”

I can be a sore loser if I suspect the playing field has not been level, and wondered whether the new owner, Tim Watts, might have served on the Creditors’ Committee as his company Network Group was owed “several hundred thousand pounds” by Wrekin. This would have given him sight of all the bids, and given him “last looks” – i.e. the opportunity to enter a final winning bid just higher than the best on the table.

When I raised this question with Ernst and Young, they said in a carefully worded reply that “at no point during the Administration has Tim Watts been a member of the Creditors’ Committee” but that “following the receipt of this (successful) offer a member of the Creditors’ Committee declared a connection to the source of the bid, and from this point forward they had no further involvement in the decision making process to sell the Gem.”

Fair enough, but this still left open the possibility that the Committee member who declared his connection could have been advising the successful bidder of the progress of the auction. However, the Joint Administrator stated that he had “no reason to believe that the purchaser of the Gem was aware of the bidding position of other parties.” It struck me, though, that a Committee member who had relayed the auction prices to a contact would be unlikely to advertise the fact.

More persuasively, Ernst and Young advised me that my bid was the third highest in the auction, so that even without the winning bid, I would still not have been successful. So it was time for me to let it go: Mr Watts’ company had, after all, lost a substantial amount of money in the collapse of Wrekin Construction, and was merely trying to recoup some of it: furthermore my £5,679 was not close to his winning bid of £8,010. His was just better pitched, although it would still be interesting to know the level of the underbid.

Mr Watts continued to be bullish about the value of his new acquisition. He said “I got a jeweller friend of mine to look at it, and he instantly spotted around twenty beautiful deep red rubies on the surface.” Based on his friend’s valuation, Watts said the ruby could be worth anything between £300,000 and £2m.

But he went on to say that the only way to know for sure will be to bring in an expert: “We have identified that we are in need of a gentleman from a mining company in South Africa to come and join us at a dinner event to take it apart. We will have a little meal for the board of directors, with a bottle of 1948 ruby port which we still have in the cellar, and he will sit and chip away all night and we will watch the rubies fall out like pomegranate seeds.”

Disappointingly, this never happened. Although he estimated breaking up the stone would generate a return of at least £50,000, he kept the stone intact, believing, on the basis of interest from enthusiasts in the US, that he could get much more by selling the stone intact.

He eventually decided to to keep it, and was quoted in 2011 saying “If I ever get down to my last fiver and need a good bottle of Shiraz then I might do something with the ruby. For the moment I am going to keep it.”

In December 2013 Wrekin owner David Unwin was disqualified as serving as a company director for ten years: two other directors were also served bans.

And, if the radio silence on the subject for the last ten years is any guide, Mr Watts has not received an offer for the gem which has tempted him to sell the gem, and he still owns the fabled Gem of Tanzania. One day we might have a better idea of its true value, which might require someone to break it apart first. But that would be a shame. We need some mystery in our lives.

Leave a comment